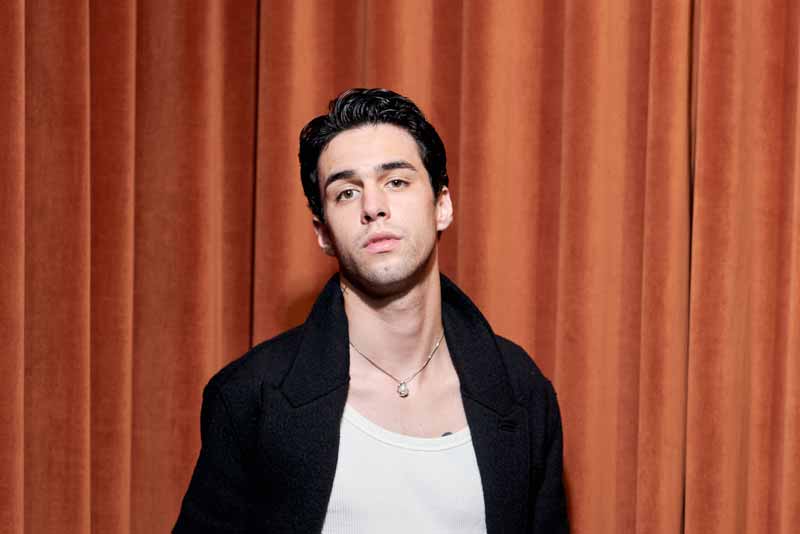

Interview — Tyron Ricketts

Stories of Value

Back in the 90’s, when Berlin-Kreuzberg used to be a lawless zone, rap artist Tyron Ricketts had a gun pointed in his face: A talk about the grimey beginnings of the Berlin hype and how the difficult relationship with his dad shaped his identity.

3. Mai 2016 — MYP N° 20 »My System« — Interview: Maxim Tsarev, Photography: Roberto Brundo

Waiting for Tyron Ricketts, I take a seat on a bench with my back to Görlitzer Straße. He has asked to meet me here at a small café across from the once infamous park. Parents with strollers, students, and senior citizens stroll by in the afternoon sun, intermingling with the few dealers who remain at what used to be one of Europe’s premier drug plazas.

Although most of the ’90s era grime has been washed away by gentrification, Kreuzberg retains an edge that can be seen in the sharp cheekbones and furrowed brows of the young men trying to scratch out a living by the park entrances. Their gaze is unique to them, furtive and cartoonishly menacing, as if they are trying to convince themselves of their own sincerity. To me they just look hungry.

The first time Tyron passes me, I don’t immediately recognize him. He zips by on a sporty bicycle with a cap slung over his eyes, and it isn’t until he tracks back in my direction that I am able to identify him. After introducing ourselves we take a seat outside, and launch into a conversation about the US, where I am from, and Tyron now lives with his girlfriend.

Maxim:

You lived in LA a while, but recently moved to New York, right?

Tyron:

There were two reasons for that. In general I left for the US because I had already done quite a lot in Germany, and I wanted a new challenge. I had just gotten done traveling the world, and didn’t want to fall back into the same old rut. Either I was going to settle down with a wife and some kids, which is hard to do without the requisite partner, or I was going to try something different. I had the good fortune of meeting Harry Belafonte around that time. He helped me get a visa for the US, so that I could go to LA. Once you’re there you need a little time to understand the culture. Even when you think that you have the US figured out, it turns out much different from what you expected. That’s also where I met my girlfriend. Actually I’d met her 12 years prior to that, but we reconnected around that time. She’s a doctor in New York, and at some point the whole long-distance thing became a drag. It was easier for me to move to New York, than for her to move to LA, since she was in the middle of her residency at the time. That was about a year ago. In New York I started working with the Belafontes, in particular with Harry on Sankofa, an organisation he started that brings together artistry and social justice. The struggle for civil rights was a hallmark of his career, and he wants to pass that spark along to later generations. People like Usher and John Legend are also involved.

Maxim:

And you’re active there in your capacity as a musician, or as an actor?

Tyron:

Neither. In the beginning I was in charge of social media content. I was responsible for photo content, interviews, and video. At the time I curated all of our channels. Now I’m a little more independent. I filmed the Million Man March. When Harry gives interviews, I film those.

Maxim:

What brings you to Berlin then?

Going to a casting with 40 other people is hard when you’ve been in film for 20 years already.

Tyron:

I still have an apartment here. I still like being here, and I don’t want to lose contact to the city. Anyway, this is where my acting career is based. In America nobody cares that I’ve done 50 films. Here that’s a good thing, but over there they want to know what you’ve done in America. They tell you to come back once you have a little more weight under your belt. Going to a casting with 40 other people is hard when you’ve been in film for 20 years already. I was at one where all I had to say was, „Shut it, Spinelli!“ For that alone you drive an hour and a half into the Valley, and then wait 30 minutes in reception. It’s humbling. Here I shoot something every now and then. I was in a film called “Kleine Große Stimme”, which was a coproduction between Austrian and German public television.

Maxim:

What’s it about?

Tyron:

The film is about a little Black boy who lives in Austria with his grandparents in 1954. He is the son of an Austrian and an American soldier, and doesn’t feel like he belongs in his town. One day he sees that the Vienna boy’s choir will be travelling around the world, including stops in America, and he decides to join so that he can search for his father there. I play his father. The movie turned out really well. With public TV movies you sometimes expect the opposite, but the director, Wolfgang Murnberger, is one of the best in Austria.

Maxim:

In the music video to your song „Neustart“ you, playing the protagonist, accuse your father of neglecting his responsibility towards you. You let him know that he left you and your mother in the lurch in Germany, with no defense mechanisms against the racism there. Does that scene have an autobiographic background, or does it reflect certain problems in German or Austrian society?

I asked my father too: »How come you never showed more interest?« It would have been nice to have a role model, growing up.

Tyron:

That scene was from another film I was in. It was a 90 minute movie that starred Günther Kaufmann as my father. Although I never had a confrontation in those same words with my dad, I did help write some of the dialogue. My parents separated when I was six, and I grew up without a Black role model in the family. After my mother remarried I was the only Black family member which meant that things happened to me that they couldn’t always relate to. The same way that you can’t fully comprehend how a woman feels in a parking garage alone at night, because you aren’t a woman, my mother and step-father couldn’t understand it when the cops harassed me. One time I was at the skate park with friends, and the police singled me out to clean up cigarette butts and empty beer cans, even though I didn’t smoke and didn’t drink. When I came home, and told my parents what had happened, they insisted that it couldn’t have been a racist thing, and that I must have done something to draw the cops’s attention. That makes you feel isolated as a kid. You can’t really blame them either, because that’s not their reality. I asked my father too: „How come you never showed more interest?“ It would have been nice to have a role model, growing up. I wouldn’t have needed to model myself on rappers at 16 then, either.

Maxim:

Do you speak English with your dad?

Tyron:

My dad is no longer alive. As a kid I didn’t speak English, although I did understand it. Later, when we reconnected in my early 20s, we spoke English.

Maxim:

Where was he from?

Tyron:

He was from Jamaica. My parents met in London in the early ’70s. He spoke some German, but with this weird Austrian accent.

Maxim:

That’s funny. When my family first moved to Dresden they sent me to a German kindergarten. I ended up speaking with this really weird Saxonian-American accent. Do you have any relationship to Jamaica, besides your blood ties?

Tyron:

I was there twice, but I didn’t really experience much of the country on either occasion. The first time I was there to see my dad, so I couldn’t really concentrate on the country, and the second time was for a video shoot. I was the host for Wordcup, a rap show on the German TV station Viva, and we were going behind the scenes of a music video shoot for Gentleman. I would like to get to know Jamaica better in the future.

Maxim:

You didn’t stop off when you were travelling the world?

Tyron:

No. I was in Canada, LA, Mexico, Costa Rica, Hawaii, Fiji, New Zealand, Australia, and Indonesia.

Maxim:

Wow, how did your travels affect you?

Tyron:

You learn a lot. You learn to adapt to changing surroundings that you can’t control. It becomes your job to react well to new challenges. I like the spontaneity of it. You quit planning things. Here you know days or even weeks in advance what you are going to be doing the next day. I learned to live in the here and now, which is one of my biggest achievements, and one that helps me each and every day.

Maxim:

In the sense that you have a better grasp of your abilities and limitations?

Tyron:

You learn to make the best of bad situations. Sometimes you only learn by doing. In Mexico a friend I was supposed to stay with left me hanging, and I had to organize shelter for myself on little to no cash. When you’ve experienced one or two of these situations, your confidence grows. A lot of people are afraid to travel on their own, because they think they won’t have anyone to talk to.

Maxim:

So when did you move to Berlin?

Tyron:

I first came here in the mid ’90s, because I had a band in Berlin, called Mellowbag. I was still living in Cologne though, since I hosted my rap show there. I’d always stay in Berlin for a couple of months, and then go back to my TV job. In 2003 I finally gave up my spot in Cologne, and moved here. I wanted to focus more on acting. My company Panthertainment which produced my TV Show also had a booking and casting department for black actors and models. We had these street teams that would go out to try and find new talent, kind of like what I’d seen going on in New York. After the music industry crashed in ’03 it just wasn’t fun anymore. So I decided to focus on what I really cared about.

Maxim:

Where would you hang out in Berlin in the ’90s?

Tyron:

My DJ’s studio was in Prenzlauer Berg by Kollwitzplatz. Back then that was still a grimey part of town. Like really grimey. He didn’t have a bathroom. You had to go out into the hallway to get to a communal bathroom. And there was no heating, so you’d have to carry up coal. There was mold on the walls. It was actually more nasty than grimey. Now it’s one of the most expensive places to live in Berlin.

Maxim:

A friend of mine who grew up here in the ’90s was explaining the gang culture from that

period to me. He mentioned the 36 Boys. Did you ever see any of that?

Tyron:

I know people that used to be OGs back then. There was a government funded integration program, called Respekt 2010, that I worked on a couple of years ago with a guy who used to be with them. Then a director that I worked with was one of the founding members. I know some of the older guys from that scene, but I was never involved in any of it. Kreuzberg used to be a kind of lawless zone, since the cops didn’t want to come in. Back then, coming from Cologne, I thought Berlin was really rough. Since I hosted a rap show, a lot of the guys here thought they had to test my cred. I had a gun pointed in my face once. Honestly, I didn’t really like it much in the ’90s.

Maxim:

When you said that they tested your cred, I imagined that you meant verbally. A gun is a little more than that.

Tyron:

It wasn’t fun. Usually it was just verbal. They would come and talk to you. And sometimes you just didn’t feel like the hassle. So one time I just ignored this guy, and kept walking to my car which I had parked in an alley. When I was pulling out he stepped in front of my car. Since I didn’t want to run him over, I stopped. Then he pulled out a gun, and aimed it at me. So I did end up running him over a little bit. It’s gotten a lot more chill. We were young then, too.

Maxim:

You said you got into hip-hop when you were a teenager?

Tyron:

Yeah, around ’85/’86. Like I said, there weren’t many role models for Black people in Germany. When rap music showed up, and the first movies started coming out, like Beat Street and Style Wars, I saw people that looked like me, doing something powerful. I was hooked. We immediately started imitating that, learning the lyrics, trying out our own little rhymes and raps. And we just kept doing that until someone actually got us a record deal. That was in ’92. Then I moved to Frankfurt, because I was studying design, and interning at ad agencies there. At the time, Frankfurt was the forefront of rap music in Germany, because of all the Americans there. A lot of the people that started it were from Frankfurt, Heidelberg, Mannheim.

Maxim:

When you started listening to hip-hop, were you listening to American rappers?

Tyron:

There wasn’t any German hip-hop until later. It was Ice-T and Kool Moe Dee. I didn’t even understand all the lyrics, so I’d make some up as I went along.

Maxim:

Because of the language barrier?

Tyron:

Yeah, they didn’t teach any of the vocabulary at school, and my father certainly didn’t use those words. Colors came out around that time, and we thought it was awesome. It’s funny, when you see that culture through the lens of film or music, you think that it’s so cool. You don’t understand where it comes from, or what it means to dress that way. When I was 21 and went to New York for the first time, all I could think was, man, I looked like these people but I am not like them at all. Living there, it’s an even bigger reality check.

Maxim:

Has that changed your enjoyment of hip-hop any? Do you prefer what some people call conscious rap?

Tyron:

I certainly prefer J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar to the really ignorant shit. I think when hip-hop started, and N.W.A would talk about their situation, it was still more progressive than it is now. They were putting it on the map. Now people do it because it sells. That’s why record companies keep picking it up. It doesn’t give people a direction. I don’t think it improves communities. Maybe that’s too easy. But no other music style uses so many words. Why don’t you make good use of what you say? Why talk about stuff that doesn’t propel anyone anywhere?

Maxim:

What if your situation is hopeless, and there is nothing realistic to propel people towards? Isn’t it natural to talk about what’s going on outside your front door?

Nobody likes standing on a corner day in, day out, selling crack. Nobody likes getting shot at.

Tyron:

That’s fine. My problem is with glorifying it. It isn’t cool to shoot someone. None of the people who live that life actually think it’s cool. Nobody likes standing on a corner day in, day out, selling crack. Nobody likes getting shot at. Black music in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s used to be different. Even if they did speak from a position in the hood, I always felt like the goal was to improve. Now it feels like people are more complacent, more willing to stay ignorant. But that’s just my opinion. I would also rather read The Glass Bead Game than listening to silly rap lyrics.

Maxim:

Do you read much Hesse then?

Tyron:

Funnily enough yes. I never read him in school, so I didn’t discover him until I was an adult, but I can relate to the way he describes things. I like how he manages to build a bridge between the rational and the mystical. Narcissus and Goldmund is one of my favorite novels. But I read other stuff as well. Right now I’m reading this Chinese philosopher, called Mencius, who lived during the times of Confucius. I like philosophy too.

Maxim:

Are you particularly interested in Eastern philosophy?

Tyron:

Yeah, I am into the old Eastern way of looking at the world. I am currently working on a documentary about my girlfriends interest in bridging western medicine with alternative healing methods. For this we want to travel around the world.

Maxim:

Did you pick that up when you were living in LA?

Tyron:

No, I’ve been interested in it longer than that. When I was in my early 20s I started doing Tai Chi Qigong because I had some problems with my hip. Western medicine told me to think about getting an artificial hip joint, so I went to get a second opinion instead, and luckily this doctor also practised traditional Chinese medicine. He put me in touch with a Tai Chi Qigong teacher. We got along well, and my hip healed up without me having to pop pills or undergo surgery. That’s what put me onto the philosophy and meditation.

Maxim:

And Tai Chi Qigong is a martial art?

Tyron:

It’s like a mix of Tai Chi which is a martial art, and Qigong which is a kind of meditation method. You have 18 slow movements, you regulate your breathing, and build up your Chi. It’s meditation, not fighting. I think the early Chinese thinkers managed to find a balance between mind, body, and soul. Sadly it’s mostly been lost on our culture.

Maxim:

What makes you happy?

I want to be a storyteller who tells valuable stories, instead of just making something shallow for quick cash.

Tyron:

I want to be a storyteller who tells valuable stories, instead of just making something shallow for quick cash. Lately, I’ve started writing and doing work behind the camera, not just acting. Right now I’m working with Christian Alvert on a film that I wrote, called Riptide. In it, I play a German doctor, played by me, who drifts out to sea after a surfing accident on the Canary Islands. He gets picked up by an African refugee boat that gets turned away by the Spanish coast guard. A couple of days later he sets out from the Moroccan shores with one other guy, trying to reach Europe as a European. I wanted to flip the script on a boat of refugees to someone from our own midst, forced to make that same journey. If I can tell valuable stories that can help to affect some kind of change, I will be happy with my work.

Tyron Ricketts is a 43-year-old actor, moderator, and storyteller living in New York City.