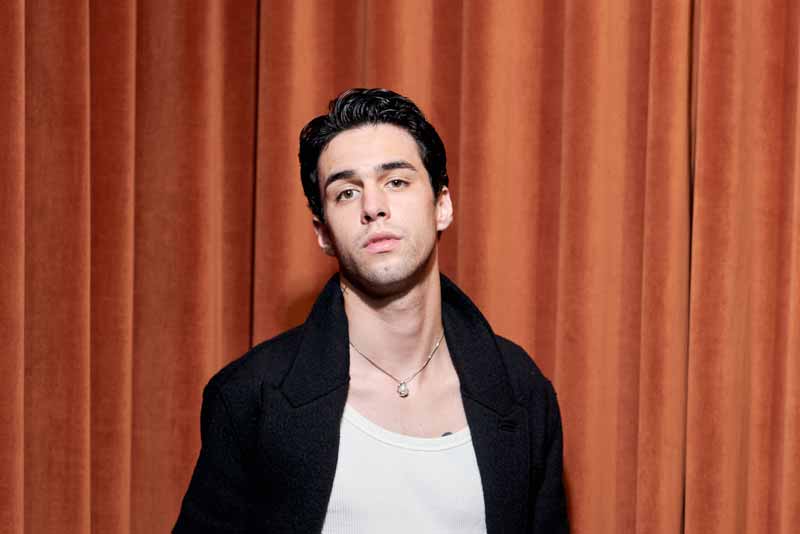

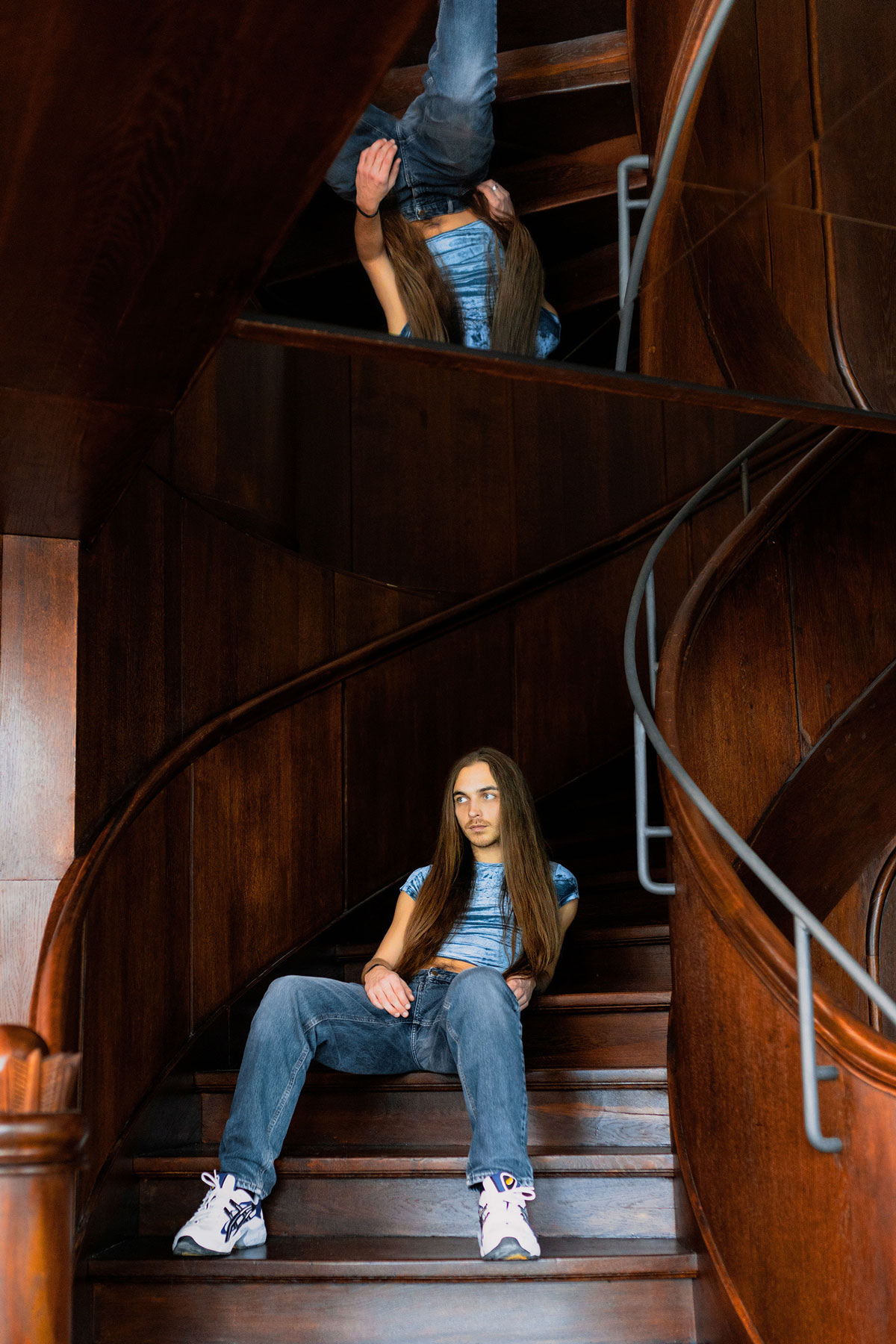

Interview — Gleb Kovalski

»Norms are always an instrument of oppression«

The queer activist Gleb Kovalski had to first flee from Belarus into political exile in Kyiv, then from the Russian war in Ukraine. Since then, the 27-year-old is stranded in Berlin. In an extended interview, Gleb tells us about the dangerous situation for queer people in Belarus, why their mother was sentenced to 15 days in prison, and how living in exile actually feels.

23. April 2022 — Interview: Katharina Viktoria Weiß, Photos: Frederike van der Straeten

After coming out at their school in Vitebsk, a city of 350,000 inhabitants in northern Belarus, classmates threatened Gleb Kovalski with a beating every day—because Gleb didn’t want to live and love heteronormatively. Teachers and adults looked away. Over the years, the once-endangered child became a brave activist, using underground queer parties to create secret spaces of safety and support for vulnerable LGBTQIA* youth.

But this fragile progress was shattered by the re-election of Alexander Lukashenko in 2020, who has ruled Belarus as a self-styled dictator since 1994 under the protection of Russian President Vladimir Putin. In the run-up to the presidential election—which was denounced internationally as neither free nor fair—opposition candidates were arrested, and votes were manipulated. The mass protests that followed ended with bloodshed, and since then the regime has been trying even more mercilessly to assert its claim to power. Gleb Kovalski and most of their fellow artists were forced into political exile due the intimidation by the Belarusian intelligence service, the KGB.

The 27-year-old lived in Kyiv for a year until violence forced them to relocate again. Since the beginning of the war, Gleb has been living in Berlin on their best friend’s couch. Our editor-in-chief, Katharina Viktoria Weiß, met the artist in Berlin at bar and restaurant Café Margarete, which is located in the same building as the Documentation Centre for Displacement, Expulsion, Reconciliation close to Anhalter Bahnhof.

»Men were forced to admit on camera their participation in the protests and their homosexuality.«

MYP Magazine:

Gleb, what can you tell us about the current situation for queer people in Belarus?

Gleb Kovalski:

After the protests in 2020, the government has destroyed all NGOs, including LGBTQ initiatives, and all the independent media that had raised LGBTQ topics. They haven’t taken away the internet from people yet, but the atmosphere in Belarusian media, cultural and educational fields has rolled back a dozen years. I’m afraid it affects the safety of queer people a lot.

MYP Magazine:

Do the police also pose a threat?

Gleb Kovalski:

Of course, especially when cops make public outings of homosexual men who attended the protests against Lukashenko with recorded videos of their “penances” obtained under pressure. In these clips, men were forced to admit on camera their participation in the protests and their homosexuality.

»After school there were crowds of teenagers who wanted to beat me up.«

MYP Magazine:

How was it for you growing up as a queer kid in Belarus?

Gleb Kovalski:

I was born and raised in Vitebsk, a mid-sized city in northern Belarus. My teenage years fall at the end of the 2000s. It was a time when social networks were just gaining popularity. At that time, there were no dating apps like Grindr or Hornet, which are popular now among non-heterosexual men. It was mostly possible to meet a guy through mutual acquaintances only, but most guys preferred to hide their sexual orientation even from other men they knew to be gay themselves.

MYP Magazine:

How do you remember your coming out?

Gleb Kovalski:

From day one, it attracted tremendous attention towards me. Not only at school, but all over the city. It also discouraged other gay or bisexual men to get in touch with me because everyone was afraid of being outed. I had big conflicts with both my classmates and teachers. After school there were crowds of teenagers who wanted to beat me up and the school administration barely managed to resolve this conflict. Instead, they accused me of provoking the aggression of those dudes by being open about my sexual orientation. And, of course, they also considered this orientation to be wrong and deviant, not worthy of talking about publicly.

»The world collapses because of creatures with unlimited power—not because of queers.«

MYP Magazine:

Why exactly did people feel so offended by you?

Gleb Kovalski:

I started just wearing elements of “female” clothing, which might seem not so remarkable in a global context, quite risky though for Belarus in 2008. And by such a violation of the “traditional” gender order, I questioned not only gender stereotypes but also broader constructs. I wanted people to ask themselves: What if I don’t do what I’m supposed to do? What if I do what I just want to do? Would the world collapse? As we can see now, the world, unfortunately, still collapses because of creatures with unlimited power—not because of queers.

MYP Magazine:

How did you find friends in this system of oppression?

Gleb Kovalski:

Those were the darkest days of my growing-up—but, at the same time, the best ones. Because being infamous in a way helped other people to find out about my existence. People who needed me as much as I needed them, and I was eventually lucky to be surrounded by the most open-minded, craziest, and sincerest people.

MYP Magazine:

Do you remember a beautiful moment of queer self-expression from your youth?

Gleb Kovalski:

My friends and I went to different schools, but after class we would meet in parks or someone’s flat when our parents weren’t home. We would get drunk on gin and tonics and go to emo band concerts, forge documents to get into night parties, fall in love, argue. But we were together to fight against a conventional world full of oppression and injustice. And I’m often nostalgic about that time because when it seems like the whole world is against you, moments of support and care from even quite random people you experience much more deeply and joyfully.

»You risked getting beaten up on the street for wearing jeans that were too tight.«

MYP Magazine:

Can you describe these feelings of unity?

Gleb Kovalski:

In Belarus, at those times, you risked getting beaten up on the street for wearing jeans that were too tight or the “wrong” length of hair. But when you hang out with your true soulmates drinking vodka on the bank of the Dvina River and singing along to insanely kitschy Katya Sambuca songs, united by the euphoria of existing in spite of all that persecution, everything else becomes irrelevant.

MYP Magazine:

How does love develop under these circumstances?

Gleb Kovalski:

I think it’s pretty cool to be able to hold hands with the person you love in a public place, or to easily have a quick but intense one-night stand—as it’s possible here in Berlin. But that can’t be compared to the feeling when you kiss your love in an abandoned humid building on the outskirts of your city late at night, where you two escaped from all eyes at least for an hour just to be close to each other without a need to hide your feelings in public. You just feel that you can’t be happier than at that moment, and that you are so far away from any countries, regimes, societies. Everything just ceases to exist.

MYP Magazine:

Do you know at what point you got into activism?

Gleb Kovalski:

In Vitebsk I was dating a guy for three years. We posted our love story pics on the internet and didn’t hide our relationship. I think this relationship can be considered as the beginning of my activism because I can’t remember anyone else doing the same back then. It was important for me to show that this relationship exists and that it’s right here among you. And that we’re, by the way, quite awesome. (smiles)

»We tried to create spaces for those identities that are also excluded from the sometimes very homonormative LGBT community.«

MYP Magazine:

You used to work for a Belarusian state TV channel. What did you experience there?

Gleb Kovalski:

In Belarus, if you study at a university at the expense of the state budget, you are obliged to work for two years after your studies at the company which you are assigned for by your university. In my case, it was the main Belarusian state TV channel. I can’t say that everything was great, but it wasn’t as awful as it seems when you watch Belarusian television now.

MYP Magazine:

How did your employment end?

Gleb Kovalski:

I got fired for supporting the national strike after the elections 2020. After that, I focused on the queer techno party series Petushnia, which I organized together with LGBTQIA* activist Andrei Zavalei in Minsk. We tried to create spaces for those identities that are excluded not only from the heterosexist world but also from the sometimes very homonormative LGBT community.

»The Belarusian electronic scene is quite male-dominated as elsewhere.«

MYP Magazine:

How can we imagine the scene in Minsk you were moving in?

Gleb Kovalski:

Realizing that the Belarusian electronic scene is quite male-dominated as elsewhere, we also intended to give a platform for self-realization of queer people, to support aspiring female and non-binary DJs. We wanted to make a melting pot where the most emancipated club kids met with peerless queer artists, musicians, and activists from different fields as well.

MYP Magazine:

Are you still in contact with your colleagues from the underground?

Gleb Kovalski:

Unfortunately, almost all of them are now scattered around the world, some are in prison. Only a very small part of our петушиного community has remained in Belarus.

»I’m just a human who tries to do less evil.«

MYP Magazine:

What role did you have in this community?

Gleb Kovalski:

I’m just a human who tries to do less evil. I don’t always succeed. I’m not sure I can make the world a better place, but I try at least to make it funnier, more exciting and worth living in, through art, texts, DJ sets, or just by me going to an agricultural state fair on high heels and in an extremely short skirt. Sometimes I feel like everything I do follows the aim to feel less lonely and maybe make someone else feel less alienated too.

MYP Magazine:

Can you tell us about a project that was very close to your heart?

Gleb Kovalski:

After a gay party in 2014, a young man named Mikhail Pischevsky was killed in a homophobic attack. My colleague Andrei Zavalei launched a public campaign called “Delo Pi_” in memory of him—because it was about much more than just one particular family’s tragedy. This case showed us how indifferent the society is and how, in Belarus, neither the law nor the justice works.

MYP Magazine:

Can you transfer that to your activism in Berlin?

Gleb Kovalski:

This story is the basis of the performance we’re working on with the HUNCHtheatre for the last two years. During the preparation of this show, we experienced lockdown, multiple emigration and the beginning of a full-scale war. At this point, we are working with an international cast along with other Belarusians. All of us are in different parts of the world, and we are trying to reflect on how ignoring one death could affect what is happening to us now, from the revolution in Belarus to the Russian invasion to Ukraine. The performance premiered at HAU Berlin on April 21, 2022. Our next show will be on April 30 at Hellerau in Dresden.

»It is very difficult—though quite exciting—to have a longing for freedom in a society that is not free.«

MYP Magazine:

How did you experience your last few months in your home country?

Gleb Kovalski:

The last year in Belarus was very significant for me as a DJ. While the whole world was in lockdown, terrible things were happening in Belarus itself. The more the political situation was getting worse, the more people were wanting to escape to the alternative nightlife world where there was no violence, no abuse, no injustice; where they could feel pleasure again, feel unity with others without the risk of being detained or killed as it happened on the streets in the daytime during the protests. For many people, parties became the source for recovery and the tool of resistance at the same time.

MYP Magazine:

How did you find the courage to face such a dangerous situation?

Gleb Kovalski:

I don’t tolerate normativity because norms are always an instrument of discrimination and oppression. On top of that, I am a very freedom-loving person. And it is very difficult—though quite exciting—to have a longing for freedom in a society that is not free. So, it has always been my pure selfish interest to take some steps in order to make people around me more free.

»I have lived in constant tension and fear, often waking up in a panic from noises on the stairwell.«

MYP Magazine:

What happened before you went into exile?

Gleb Kovalski:

I never thought that I would leave Belarus for long because I always felt needed in this place. I wanted to influence many things and I thought I knew how to do it. I couldn’t imagine what exactly was going to happen that would make me emigrate. Since August 2020, like many people, I have lived in constant tension and fear, often waking up in a panic from noises on the stairwell, never picking up the intercom, and often looking out from the window to be sure no one’s there before leaving the house. At the same time, I had no idea that this could be a reason for emigration; I perceived it as temporary precautions while the political regime was changing.

MYP Magazine:

How did the authorities increase the tension?

Gleb Kovalski:

One of our team members was visited by KGB officers at their flat in Minsk. The officers presented a huge folder with personal information including details about our theatre activities. They asked about previous and upcoming shows, about the actors’ political views, and their possible attendance in protests. In the end of that “home interrogation” they “warned” them of consequences of any further activity by our team. I think that day can be considered as the end of the Belarusian branch of HUNCHTheatre because after that, we’ve never met again in Belarus all together.

»When you live in this hell every single day, you get used to it.«

MYP Magazine:

Why and when did you have to leave your home country?

Gleb Kovalski:

The overall situation in the country abruptly deteriorated in February when searches began to take place in the flats of my close friends, including the most apolitical ones or those who do not even live in Belarus. Then it became clear that the darkest times had come, and I agreed to an offer from my friends to wait out a month or two in Kyiv. I left taking with me a pair of sweaters and underpants, in absolute confidence that this was just a temporary measure, but I never returned to Belarus again.

MYP Magazine:

How did you feel in these first months in exile?

Gleb Kovalski:

Every day the situation in Belarus was getting worse and worse. When you live in this hell every single day, you get used to it—and hell seems tolerable. But when you look at it from the outside, being in a more or less safe place, coming back seems just suicidal. So, I didn’t really have a choice.

»Your brain still refuses to even allow the fact you might not return to the place that has become your home.«

MYP Magazine:

How did you experience the outbreak of the war?

Gleb Kovalski:

In the last few months in Kyiv, I was going through a severe depressive episode related to losing my home, feeling displaced, and having a lack of old close friends around. On February 23, 2022, when all the people in Ukraine were talking only about the potential threat of a full-scale Russian military invasion and were endlessly posting stories with maps of bomb shelters, I posted on Instagram an apology for feeling absolutely nothing about the war and not being able to get involved in this information flow because of my depressed state. The next morning a full-scale war began.

MYP Magazine:

How did you react?

Gleb Kovalski:

I tried to leave the same day. There was no panic, it was calm in Kyiv, and I didn’t think about whether it would be as calm in the next few days. I just wanted to calm down my mother who was calling me hysterically every hour from Belarus, so I decided to go to my friends in Warsaw or Berlin for a week or more until it became clear what was going on. The funny thing is: I barely filled my suitcase because I had no doubt that I was going away for a short period of time. A year ago, when I was leaving Belarus, it was the same. And now even with such a fresh experience under your belt, your brain still refuses to even allow the fact you might not return to the place that has become your home. I didn’t have that option in my mind.

MYP Magazine:

What happened during your flight?

Gleb Kovalski:

I succeeded to leave only the next day. The road was literally burning behind me. We would pass some towns that were quiet and peaceful and then, one hour later, we would read on the news that a bridge had been blown up or bombed. I was lucky to get from Kyiv to Warsaw in only 28 hours. Many of my friends spent days at the border and still couldn’t get into the EU. From Warsaw, I went straight to Berlin because my best friend Jan and his husband were waiting for me there, ready to provide accommodation and a cozy atmosphere and to take care of me.

»My mother and thousands of people like her are stranded in a country where their own state is at war against them.«

MYP Magazine:

What happened next?

Gleb Kovalski:

I slept well for the first time in three days and decided to call my mother in the morning. She didn’t answer the phone. A few minutes later my cousin texted me that my mom had been detained on the street by the police. She is not a civic activist and has never participated in public political rallies. On that day she simply went out in the street wearing a mask marked “Stop War,” because she wanted to do something, even the very least, so that maybe she could deal with her own pain and helplessness. She was sentenced to 15 days in jail. This is all you need to know about the level of repression in Belarus.

MYP Magazine:

How do you look upon the role of Belarusian citizens in the context of war?

Gleb Kovalski:

When rockets were flying from Belarus to Ukraine, many Ukrainians called on the Belarusians to stop it and overthrow the dictator. Many called us accomplices of the Russian government. But the story of my mother and thousands of Belarusians shows that in Belarus, just going out of your home is enough to be sent to jail. Nevertheless, Belarusians have paralyzed the railways to stop the movement of Russian military forces to the border of Ukraine. They are risking the death penalty and endure tortures every day in prison for this. And Belarusians abroad create volunteer military units and fight on the side of Ukraine against the Russian occupiers. Hundreds of Belarusians create organizations, volunteer at the borders, evacuate Ukrainians, and organize humanitarian aid.

MYP Magazine:

Why is it so important to highlight that?

Gleb Kovalski:

It hurts watching how countries of the EU are closing their borders with Belarus and denying visa applications from Belarusians, or at least making the process as complicated as possible. My mother and thousands of people like her are stranded in a country where their own state, not an external one, is at war against them. And they are losing their last chance to save themselves.

»Coming to Berlin to hang out at a club is not the same as running away from the war.«

MYP Magazine:

Has living in Berlin changed some of your values or views on the world?

Gleb Kovalski:

I can’t say that I live in Berlin, as in live a real life. Everything is quite surreal at the moment, and I don’t feel I belong to any place. I first visited Berlin six years ago and since then, I’ve been here many times on different occasions. But coming to Berlin to hang out with friends at a club is not the same as running away from the war and getting into the total unknown and uncertainty of my future.

MYP Magazine:

How are you trying to deal with that displacement?

Gleb Kovalski:

I force myself to enjoy the beautiful people around me, the wonderful parks, the unusual and pleasant atmosphere of the neighborhood I’m staying in. But I feel almost nothing. My body is here, but I live in my trauma, my soul is endlessly flitting between Vitebsk, Minsk, Kyiv, and Berlin, sometimes getting stuck for several days in Bucha, in a bomb shelter in Kharkiv, in broken Mariupol.

MYP Magazine:

What can you tell us privileged people about the emotions of exile?

Gleb Kovalksi:

A forced escape is not a planned emigration when you move into a bright clean apartment and shelve your favorite stuff in pleasant anticipation of a new life. A forced escape, no matter from what country, is destruction, pain, and fear.

#glebkovalski #hunchtheatre #mypmagazine

More about Gleb Kovalski:

More about HUNCHtheatre Belarus:

instagram.com/hunchtheatre

Next show on April 30 at Hellerau, Dresden

Photography: Frederike van der Straeten

Interview & text: Katharina Viktoria Weiß

Editing: Benjamin Overton