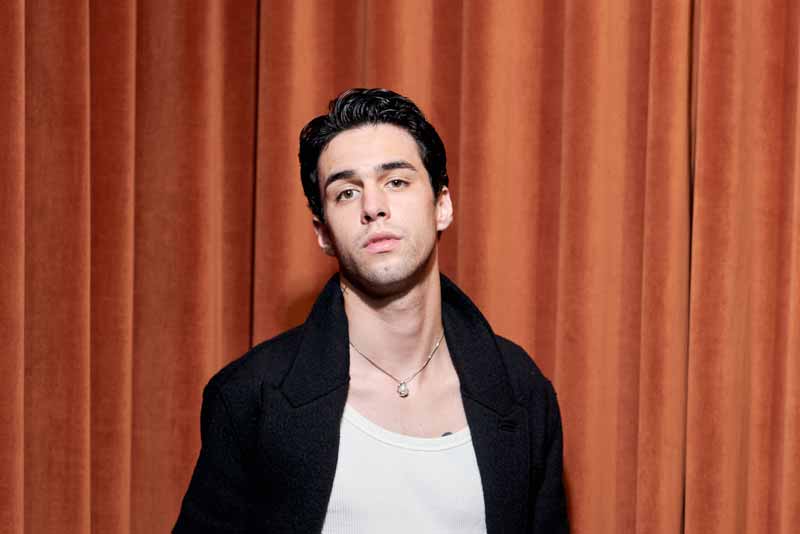

Interview — Fred Roberts

»It takes a personal story to help someone else«

The British singer-songwriter Fred Roberts is an exceptional phenomenon for two reasons. Firstly, the 21-year-old creates music that simply sticks in the ear and sounds as though he has been doing nothing else for decades. And secondly, with his unflinching openness about his own emotional world, he serves as a role model for many queer kids around the world. We met him for a very personal interview about living in disguise, the power of Troye Sivan, and an artistic vision that is much more than writing self-help songs.

11. April 2024 — Interview & text: Jonas Meyer, Photography: Steven Lüdtke

What is a role model? The term, which today seems to be a natural part of our linguistic usage, was first coined by the sociologist Robert Merton back in the 1950s. Merton described role models as individuals who serve as examples for others to emulate, and he proposed that they play a crucial role in the socialization process, particularly in the formation of aspirations and goals among individuals.

One of these individuals is certainly Fred Roberts. The 21-year-old singer-songwriter from England has been a beacon of hope for many queer teenagers around the world, at least since he gave them a deep insight into his inner self with Disguise, only the third single he’s ever released and part of his debut EP Sound of My Youth. In his own words, he addressed this song to the boy who said he’d love him—if Fred were a girl.

However, this description is somewhat narrow for two reasons. Firstly, Fred’s role model appeal is not just limited to the younger generation. In general, he offers an emotional refuge to all those who have experienced the need to disguise themselves, hiding who they truly are and who they love. And secondly, even more importantly: at the age of 21, Fred Roberts can already be regarded as a serious artist who makes damn good music—music that wants to stay in your ears once you’ve heard it.

And so, we make the same mistake here, as many others do, which should be avoided at all costs when approaching an artist journalistically: we put the sexuality aspect first, not the music. And at the same time, it has never been more important to have queer individuals who use their art and outreach to provide more visibility for a group of people, many of whom are still socially stigmatised, persecuted and marginalised today.

A few weeks ago, our publisher Jonas Meyer met Fred Roberts in Berlin for a very personal conversation.

»This song is about one of the most vulnerable experiences I ever had.«

Jonas:

Disguise, the latest single you released, is a song “for the boy who said he’d love you if you were a girl.” You said on Instagram that you’d wanted to tell the story of this song for a long time. How do you feel, now that the story has finally become public?

Fred:

Even though the first two singles, Runaway and Say, also draw from personal experiences, Disguise was a big step further of being very specific: this song is about one of the most vulnerable experiences I ever had. The fact that this story is now out in the world feels exciting, because the reason why I make music is to let people who are going through the same shit know that they’re not the only ones who feel this way. In my opinion, it really takes a personal story to help someone else. It can make people feel less scared. Music is so transformative, you know? The flip side is: I feel that the story is not owned by me any more. That’s very weird, but that’s also what makes the song so special.

»Everyone in the world now knows what happened.«

Jonas:

Don’t you feel somehow exposed, telling the world this very intimate story?

Fred:

Kind of, yeah… especially with being so vulnerable in the lyrics. Everyone in the world now knows what happened. Even though the whole song is an artistic product, which means that I’ve slightly stepped away from who I am as a person, it’s still my name on it in the end; it still reveals my very own experiences and intimate feelings. But what would the alternative be? I guess it’s easier to not hide behind the fact that I’m the one who’s actually lived through it.

Jonas:

Luckily, this story only provides a very small insight into your personal life and uncovers 0.1 per cent of who you actually are…

Fred: (smiles)

But I’ll keep writing to fill in the gaps!

»The full picture of what I want to be as an artist is yet to be drawn.«

Jonas:

Do you sometimes get the impression that people who listen to your music think they know you 100 per cent? Especially now that they think they can follow you every step of the way on Instagram.

Fred:

Isn’t that what we all do when we like someone’s music? I think it’s nice that so many people are interested enough in getting to know me and my music, and it’s lovely to see that they’re connecting with the songs and everything… I mean, I’ve only released three singles, and my first EP is in the starting blocks!

But I’ve got so many other songs I’ve been writing for probably two years now, which means that I’ve got this backlog of different paths I’ve gone down. So, yeah, there is definitely a lot more to build, the full picture of what I want to be as an artist is yet to be drawn. Until then, this whole situation is like a new world for me.

»I’m basically saying: I wish I was somebody else that you could love—but I’m not, unfortunately.«

Jonas:

Some of your fans find that Disguise sounds like a song that could accompany the final scenes of a coming-of-age-film. What images did you yourself have in mind when you wrote the song?

Fred:

I’ve always been a storyteller, I really enjoy that. The way I got into songwriting was literally like this: I would have an experience, I would write about it, and then I’d sit in front of a piano and just play some chords, literally speaking the story. That has always been my process.

My favourite film is Call Me by Your Name—with its landscape, all its nostalgic elements and the dark nights—and I feel that the sound of Disguise evokes that same imagery. When I think of the end of the film, when Elio’s sitting by the fireplace after he got off the phone with Oliver who told him that he’s getting married—that’s definitely the world Disguise comes from. In the part where I sing, “Do I wish I was somebody else?”, I’m basically saying: I wish I was somebody else that you could love—but I’m not, unfortunately. I think that’s the emotion that relates to the one expressed in the film, the image of crying in front of the fireplace.

»I feel that the nature of a slower song allows me to tell more stories.«

Jonas:

After two up-tempo singles, Disguise shows a more thoughtful and dreamy side of you. Would you say that this aspect reflects your personality more? Or is it the other way around?

Fred:

Both sides reflect my personality, I’d say! I just love throw-yourself-around songs like those by my favourite band, The Killers. I’m totally into the anthemic nature of music. So that side of it is definitely one half of me. But then, there’s a song like Disguise, and I’ve got a few other guitar ballads coming up. That just gives me the opportunity to be more real with the lyrics. I feel that the nature of a slower song, with atmospheric, intertwined sounds, allows me to tell more stories.

But even though you’re getting more of me in Disguise than you’re probably going to get in Say or Runaway, these two other songs are also extremely important for me in building the world in which I want my music to exist.

»If I were to produce it myself, it wouldn’t sound anything like this.«

Jonas:

Your songs have a very high production quality and sound like you’ve been making music for decades. But you only released your debut single in April 2023. Would you say you are a perfectionist? Or is it the people you work with?

Fred: (smiles)

I’m a perfectionist, but I’m not the one who produces the music. I’m very lucky to have Andrew Wells by my side: he’s like my anchor in the projects, even though he lives overseas. I met Andrew during lockdown through other people and we connected, but the only music I had were some rough demos I’d done on a Zoom recorder. That didn’t put him off and he still wanted to work with me. He was so passionate about building a soundscape and finding the right vibe, it was just incredible. And this guy is still pure magic. Even when we write a song over the course of a day, he often finishes it at the end of the same day. As much of a perfectionist as I am, he surpasses me by far. And if I were to produce it myself, it wouldn’t sound anything like this.

»It’s hard keeping true to yourself when you want as many people as possible to listen to your music.«

Jonas:

How important is it to create a brand around your music nowadays? Is there a danger of losing your own edginess and personality in the process?

Fred:

I think I’d be stupid if I always tried to write songs with a goal in mind. But of course, I’m aware of why certain songs exist. Runaway, for example, was quite big on the radio in Germany. That’s pretty cool, but I didn’t write the song to be successful in a specific market and in a specific medium. I was just lucky that it appealed to people’s tastes. Something like that just happens, or it doesn’t. But whatever—it doesn’t influence the music I love to make.

It’s hard keeping true to yourself when you want as many people as possible to listen to your music. If you really want to be successful, at least in a commercial sense, you have to write songs that reach out. But the second you write a song with a specific purpose, like going viral or taking off as a massive radio hit, that’s when the magic disappears.

For me, writing a song is only for the sake of writing it. When I come to the studio, it’s important for me to bring a story I really care about. Then Andrew and I elaborate it together, just knowing that we’ve got certain influences and certain songs that we want it to sound like, and then it turns into whatever it turns into. That’s all.

»Something deep inside me also wanted me to make music, but I wondered: How do I actually do that?«

Jonas:

When in your life did you realize that making music is a vital outlet for your emotions?

Fred:

During lockdown. I mean, I was already on a TV show in the UK just before the first lockdown; that’s how I got a little bit of a platform and how I made a few connections in the industry. But I hadn’t written a song before. I had just sung for a little bit, including in a school choir. But nothing serious. After lockdown happened, I found myself playing Xbox for the first six months. I was still at school at the time and about to finish it up. Something deep inside me also wanted me to make music, but I wondered: how do I actually do that? My mum just said: “You got to write your own stuff, you know?”

»If no one in the world existed, I think I would still feel the need to document my emotions in a song.«

Jonas:

Your mother used to be a performer, your dad’s a graphic designer. What influence did the creative professions of your parents have on your own artistic development?

Fred:

My mum was the one that got me started and playing piano, she was one that pushed me to get into music in the first place, and she’d sit over me while I practised and so on. Without her, I probably wouldn’t be able to write a song.

Overall, having two parents that both understood the need for a creative outlet was really important. I think it might be more difficult if they’d work in finance, for example. Not that it’s a worse job, but I think if you’re a parent working in the creative field, you have a finer instinct for when your child develops a quiet voice in their head that asks them more and more often: do you want to be a singer? Honestly, this wasn’t a big dream I had from a young age. But there was this constant voice that got louder and louder, and my parents instinctively understood. Their message was: “When there’s something inside of you that you want to let out, just do it and see what happens.”

Jonas:

Isn’t that the essence of art?

Fred:

I guess it is! And in this context, it doesn’t matter whether anyone is listening to you. If no one in the world existed, I think I would still feel the need to document my emotions in a song, like other people do in a diary, for example—although I would be a bit upset by now if absolutely nobody listened. (smiles)

It still feels kind of weird. There’s nothing more special to me than making a song about a specific experience and then getting home after a session, just being in bed, putting my headphones on and being instantly taken back to what I was feeling in the moment it happened.

»The song triggered something deep inside of me.«

Jonas:

A few weeks ago, when the whole world seemed to be posting their Spotify Wrapped, including you, it turned out that you and I have something very important in common: Last year, we both spent endless hours listening to Ryan Beatty’s new album, Calico. What do you like about it?

Fred:

This whole record is just perfect! I’m surprised it’s not being promoted more. Maybe it’s because Ryan Beatty is no longer perceived as a traditional artist like he was a few years ago. He was something of a pop star, and he was releasing music that’s far different to what he’s creating now.

For me, Calico kind of soundtracked my entire summer last year. This record is just beautiful from beginning to end, its soundscape is phenomenal, and it’s been a long time since I skipped any songs on an album. I’m absolutely sure that this record will stay with me for a very long time… What’s your favourite song on it?

Jonas:

It’s Ribbons. I remember sitting on the bus to our office early in the morning and listening to it. Suddenly I started crying—but I couldn’t understand why it touched me so much.

Fred:

Oh, I definitely know what you mean. Ribbons is just brilliant. I had the same experience with Black Friday by Tom Odell. I guess that was my top song of the year 2023—the way it builds up just blew me away. When it came out, I was in Hamburg playing my third show ever. I’d been through a breakup a few months ago, and I remember lying in bed after going out on the Reeperbahn. It was 2 a.m. and I had the song on full blast, absolutely the same experience as yours. I didn’t know why I was feeling any of this, it triggered something deep inside of me.

»Watching Troye Sivan’s music videos, it was the first time I’d seen two boys or men be with each other.«

Jonas:

Even more than Ryan Beatty, another music artist—a certain Troye Sivan—has changed your life. Can you tell how?

Fred:

My first contact with his music was when I discovered him on YouTube, watching the videos of his Blue Neighbourhood Trilogy. It was the first musical discovery of my life that wasn’t through a friend or my parents or someone else recommending me any music. I was hooked from the very first second. I saw this amazing Australian boy who was making wonderful music, and I was like, who is this? From that moment, I literally absorbed his songs.

At that time, I was 14 or maybe 15 years old, going through a period of my life figuring out who I was. Watching Troye Sivan’s music videos, it was the first time I’d seen two boys or men be with each other…

Jonas:

… and that was something so new for you?

Fred:

Not that I wasn’t aware of this beforehand—I had already seen it in my personal life—but until then, it had never appeared in the media that I was actively consuming. Or, to put it differently, I had never immersed myself in the storyline of a gay couple.

»The confusion or loneliness that comes with being gay was something no one had ever talked to me about before.«

Jonas:

What effect did that have on you?

Fred:

That specific experience was very important for me to find my own identity as a gay man. Of course, I knew already what it meant to be gay, and I already knew that I liked boys, but that was it. Everything else that comes with that—the confusion or loneliness, for example—was something no one had ever talked to me about before. Troye Sivan was the first one who, through his music and videos, spoke openly about all the emotions and experiences I personally could relate to. He showed me that I wasn’t the only person in the world who had fallen unhappily in love with a boy. That was magical.

I guess knowing that there’s an artist out there that is being so open and vulnerable about certain issues kind of paved my own artistic way. Apart from that, he broke so many boundaries of what can be talked about today, especially with his new album and the visuals. I mean, obviously, being queer is more accepted in the world now than it was just a couple of years ago, but there’s still a long way to go.

»My sexuality isn’t my whole life. There are so many different parts of me that define who I am as an artist.«

Jonas:

Absolutely. I myself grew up as a gay kid in a small town, and I always thought my generation would have been the last one growing up without any queer role models or a public conversation about people who do not conform to the heteronormative ideal. Then, preparing for today’s interview, I learned that you when you realized that you were gay, you also didn’t know who to tell or how to articulate it because the conversation still didn’t seem to exist at that age. How do you perceive the situation for queer kids in our society today? What do you hear from people who get in touch with you?

Fred:

When I released the first two songs, before Disguise, it wasn’t obvious what I’m talking about. And to be honest, I also didn’t want to explain…

Jonas:

You don’t have to explain anything either.

Fred:

I know. My sexuality isn’t my whole life. There are so many different parts of me that define who I am as an artist. But then the moment came, with Disguise, when I thought that telling my story was kind of important. I started to talk about my life and to explain what the song was about, which also changed the perspective of my past songs, I think.

The people’s reactions were just overwhelming. I’ve received so many messages from people saying, “You’ve put into words how I’m feeling”, “You express something I didn’t know how to express”, or just “Thank you for sharing this story”. When that comes from someone older than me, it’s particularly touching. I’m in a place right now where it’s okay to be gay. Many older people weren’t allowed to experience that in their youth.

»I’m aware that just because I’m personally doing well, it doesn’t mean that all queer kids are in a good situation.«

Jonas:

Many teenagers today are still not allowed to do that.

Fred:

Right, especially those who live in smaller towns or villages and not in big, diverse cities. I’m aware that just because I’m personally doing well, it doesn’t mean that all queer kids are in a good situation. It’s often quite the opposite. Many of them are going through a lot of shit right now, especially when I think of trans kids in the UK these days. Listening to their stories is heartbreaking for me because they are still subject to a lot of stigma. But at the same time, knowing that I’m able to connect with them through my music is more than heartwarming. I never had a same-age role model when I was growing up, and it didn’t feel okay to be gay until I came across Troye Sivan. If there’s even one teenager I can do something similar for or give a voice to, that would be also magical and make me happy.

»In environments where someone might have something against gay people, I tend to hold back from shouting it out.«

Jonas:

Interestingly, there isn’t just one coming-out for queer people. Rather, it is an ongoing process with many coming-outs almost every day. For example, telling you in a question a few minutes ago that I grew up as a gay kid was a conscious decision to come out to you.

Fred:

I totally agree. I’ve been in a few writing sessions where I met some people I haven’t worked with before. This is just a very small thing to tell, but when they were suggesting lyrics including the word “her”, I had to say: “Oh, sorry guys, I can’t sing that, I’m gay.” But sometimes I don’t say it and just change the lyric, you know? This is also a conscious decision in favour of or against coming out—because when you’re in a room with other people, you can’t just leave. (laughs)

But seriously—it still doesn’t feel natural at all having to announce your sexual preference in front of other people. It’s such a weird thing. But at the same time, it’s very important, because it adds context and it allows other people to understand you better. But it remains a conscious decision. And in environments where someone might have something against gay people, I tend to hold back from shouting it out. In an ideal world, everyone would get along with everyone else and it would be okay for us all to love each other.

»In our society, talking about their emotions is still not a thing for men.«

Jonas:

Four years ago I had the chance to talk with your colleague Sam Fender about his song Dead Boys. He said: “We still think it’s bullshit for boys to cry. We still try to emasculate them by saying, ‚Don’t be a fag‘ or ‚Don’t be a little girl‘, and simultaneously we accuse others of being sexist. Isn’t that ridiculous? I spent an entire life around that kind of bullshit bravado that people haven’t got rid of.” Is that still the case, in your experience?

Fred:

Dead Boys is a very sad song because it deals with the high suicide rate among young men in the UK. However, when it comes to my personal experience with toxic masculinity, the saying “Men don’t cry” is one that I’m very familiar with. I went to an all-boys school and for a lot of the time that I was there, it was a progressive school. Nevertheless, through my teenage years, I masked certain elements: my behaviour, for example, or the way I dressed. I just wanted to fit in. And even though I was in this progressive place, I personally experienced that that language still exists and that boys aren’t used to talking about their emotions with each other. In our society, this is still not a thing for men, and it seems to have been buried in them for generations.

»Troye Sivan’s achievement is to push the boundaries of what is usually thought of as a male pop star.«

Jonas:

I’d like to come back to Troye Sivan and Ryan Beatty, because they both play artistically with the topic of toxic masculinity: Troye in his video for the song Rush, Ryan in his album artwork, which is designed around the photography by Peter de Potter. Would you say that an artistic approach is the only way to change something when it comes to that outdated idea of being a real man?

Fred:

I don’t think it’s the only way but it’s one of the possible ways. Troye Sivan, for example, is pushing the boundaries on what a male pop figure can wear. When I was growing up, the idea of a male pop star was pretty clear. And today, the image you have in your head when you picture Shawn Mendes or Justin Bieber is a cool guy wearing hoodie and trousers and singing songs…

Jonas:

… nothing against comfy hoodies!

Fred: (laughs)

No, no, of course not, I like wearing hoodies myself. By the way, that’s another stigma: that all gay kids like flamboyant clothes. But Troye Sivan’s achievement is to push the boundaries of what is usually thought of as a male pop star. He’s stepping outside of the male stereotype and the role ascribed to male musicians. The same goes for Ryan Beatty’s album artwork. I think what they do is really important because their message is: “Don’t be afraid!” When someone sees artists like them talking openly and being vulnerable, they might also find the courage to do so personally—maybe even if they’re a straight man.

»My artistic vision is much more than writing self-help songs.«

Jonas:

I found the following quote from you: “I write songs with the specific intent of helping someone who is going through the same experience.” Do you sometimes feel a certain responsibility that comes with such a promise?

Fred: (ponders for a moment)

I’m still very early on in making music and plan to do this for a long time, but according to the messages I get, it seems that I’ve already impacted some people’s lives. But I don’t know if I feel a special responsibility here, because that’s exactly why I make music: I want to help people. But that’s not the only reason: I also just want to play concerts and get people dancing. Sure, I’m still telling my personal stories with the songs, and when someone can connect with that, it’s brilliant. But if someone just likes the sound and the energy of my music, that’s just as good. My artistic vision is much more than writing self-help songs.

»When I put that in my headphones, it feels like everything’s good.«

Jonas:

From my point of view, there is almost nothing more intimate than entrusting another person with the music in which you find your own emotional refuge. Is there a song or a band that you only recommend to someone if you really like them?

Fred:

Black Friday by Tom Odell, which I have already mentioned, is perhaps a little too melancholy. That’s why I recommend another song that you certainly haven’t heard of in Germany. It’s called Dakota by Stereophonics, a song that has been massive in the UK. I played it in a really slow version at my first live show and it’s also the song I usually listen to before playing a show. It’s like a warm-up: I put on my headphones, go to a private room, and just jump around.

The message in it is actually really sad. It’s about not understanding what the hell happened with a relationship. But it resolves and the song ends with countless repetitions of the line, “Take a look at me now.” It’s just euphoric, in a sense. When I put that in my headphones, it feels like everything’s good—at least for the moment.

More from Fred Roberts here:

Photography by Steven Lüdtke:

Interview and text by Jonas Meyer:

Copy editor: Jem Nelson