Beatsteaks

Interview — Beatsteaks

Wild Years Revisited

Die 90er, ein wildes Jahrzehnt: Die DVD wurde erfunden, Windows 95 kam auf den Markt, Robbie Williams verließ Take That und eine Band namens Beatsteaks gründete sich in Berlin. Zu ihrem 20. Jubiläum schwelgen wir mit den legendären Musikern in Nostalgie und lassen die wilden Jahre wieder aufleben.

29. November 2015 — MYP No. 19 »Mein Protest« — Interview: Jonas Meyer, Fotos: Maximilian König

„Dieses Haus stand früher in einem anderen Land.“ – Es ist dieser eine Satz, der sich in diesen Minuten in unseren Köpfen ausbreitet und dabei nicht den Eindruck macht, als wolle er so schnell wieder verschwinden. Man kennt den Satz aus der Brunnenstraße in Berlin-Mitte, wo er in riesigen Lettern auf die Fassade eines Hauses geschrieben steht. Von dort erinnert er an eine Zeit, die gerade einmal ein Vierteljahrhundert entfernt liegt. 25 Jahre – was ist das schon?

Ein Mittwochnachmittag im September. Wir stehen vor dem „Funkhaus Berlin“, einem denkmalgeschützten Gebäudekomplex im Bezirk Treptow-Köpenick, in dem von 1956 bis 1990 der Rundfunk der DDR seinen Sitz hatte. Das alte Funkhaus liegt direkt an der Spree, am Ufer gegenüber erstreckt sich großzügig der Plänterwald. So hat die ganze Szenerie fast etwas von Naherholungsgebiet, von Naturidylle außerhalb der Stadt. Da fällt es im ersten Moment auch gar nicht auf, dass der Zahn der Zeit sichtlich an den gewaltigen Natur- und Backsteinfassaden genagt hat.

Dass dieses Gebäude einmal in einem anderen Land stand, wird uns erst bewusst, als wir über den Haupteingang den ehemaligen Verwaltungstrakt betreten. Auch wenn der Marmor im Foyer, der zum Teil noch aus der Neuen Reichskanzlei stammt, versucht, den letzten Glanz aufrecht zu erhalten, ist es doch in erster Linie ein Gefühl von Vergangenem und Verlassenem, das hier über allem schwebt.

Mit dem Aufzug fahren wir von der Eingangshalle in eines der oberen Geschosse und stehen nach wenigen Minuten in einem großzügig geschnittenen Büro samt Vorzimmer. Wir trauen unseren Augen nicht: Abgesehen davon, dass der Teppich deutliche Verschleiserscheinungen zeigt, wirkt alles, als hätte hier gestern noch jemand gearbeitet. In diesem Fall scheint es wohl ein hochrangiger Funktionär des DDR-Rundfunks gewesen sein. Wer ihn sprechen wollte, musste nicht nur an der Vorzimmerdame vorbei, sondern auch an einem endlos langen Konferenztisch mit einem guten Dutzend Stühlen. Am Ende dieser Strecke erwartete den Besucher ein breiter Schreibtisch. Wer hier auf dem Chefsessel saß, hatte nicht nur eine tolle Aussicht, sondern auch eine Menge Macht. So drängt sich der Gedanke auf, dass in diesem Raum nicht nur Musikerkarrieren angestoßen wurden, sondern auch beendet und damit Schicksale besiegelt.

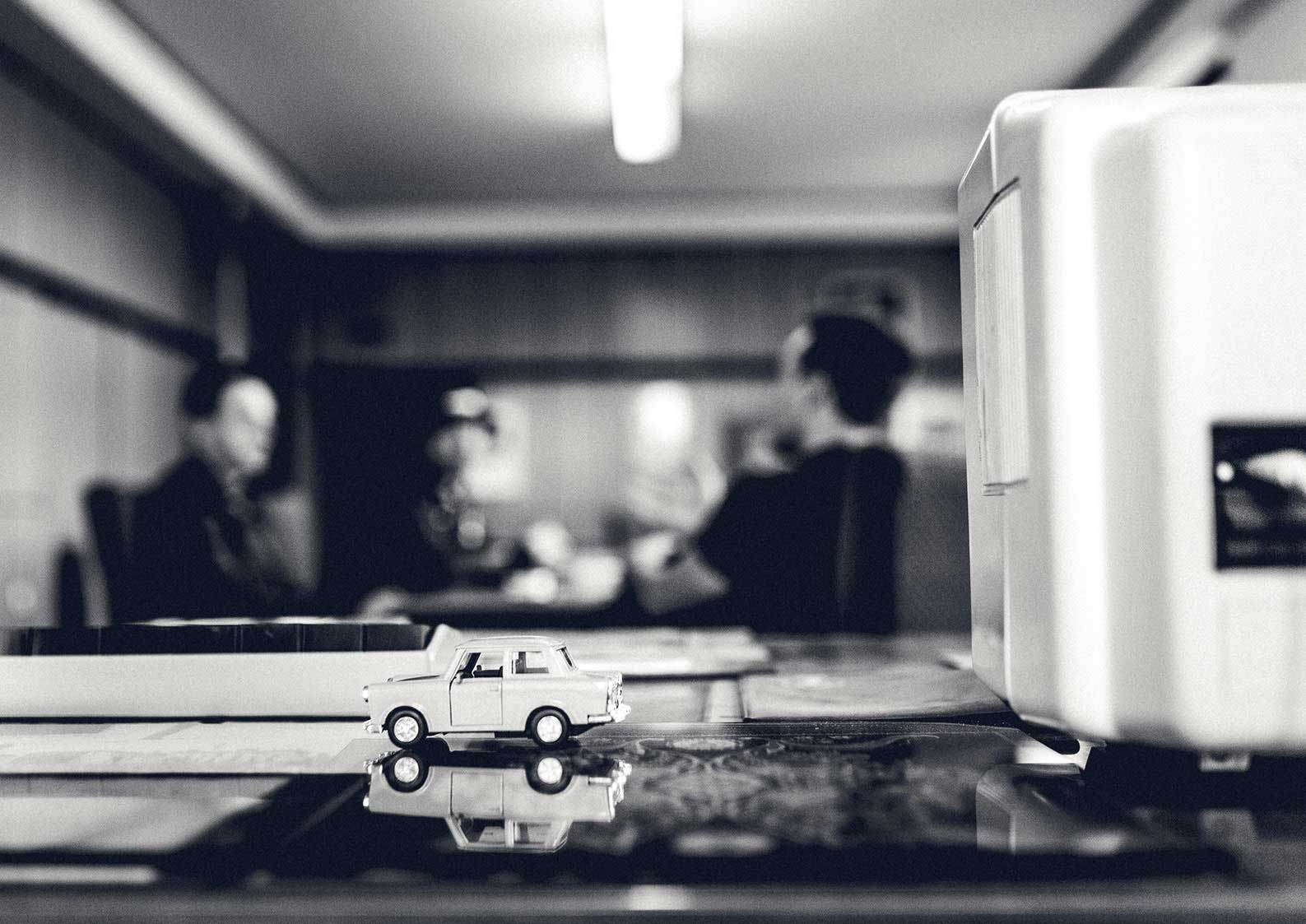

Aber diese Zeiten sind vorbei. Was bleibt, ist Ostalgie – zumindest hier. Wohin man schaut und greift, gibt es die DDR zum Anfassen: Schreibmaschinen, Fernseher, Telefone, Radios, Bücher, Kalender, Unterlagen und etliche Skurrilitäten. Alles Originale, versteht sich. Sogar die Gardinen sind noch in dem Zustand, indem sie waren, als man sie zum letzten Mal zugezogen hat. Darüber hinaus gibt es natürlich Honecker-Devotionalien aller Art. „Vorwärts immer, rückwärts nimmer.“ Oder umgekehrt.

Plötzlich sind einige Stimmen zu hören, die Tür öffnet sich. Im nächsten Moment stehen Arnim Teutoburg-Weiß und Peter Baumann von den Beatsteaks im Raum. Mit einer Energie und Offenheit, die dieses Bürokratenzimmer seit 1956 wohl nicht allzu oft erlebt hat, kommen die beiden Musiker auf uns zu und begrüßen uns. Als hätten sie im Sturm den Raum für sich erobert, greifen und begutachten sie diverse DDR-Artefakte, ziehen Grimassen und lümmeln sich auf dem Chefsessel herum.

Die Jungs haben Spaß, daran besteht kein Zweifel. Dabei verströmen sie trotz ihrer Energie eine angenehme, fast ansteckende Gelassenheit. Vielleicht ist es diese Mischung, die dafür sorgt, dass die Band seit mittlerweile 20 Jahren erfolgreich ist. Ihre gemeinsame Geschichte beginnt Mitte der 90er, genauer gesagt im Jahr 1995. Manche beschreiben diese Zeit als wilde Jahre, vor allem in Berlin.

Jonas:

Wir haben einen kleinen Rückblick auf das Jahr 1995 mitgebracht. In diesem Jahr rollte beispielsweise der erste Castor-Transport durch Deutschland, Christo verhüllte den Reichstag, der BVB wurde deutscher Fußballmeister und Robby Williams verließ Take That. Welche Erinnerungen habt ihr an das Jahr 1995?

Arnim:

Stimmt, diese Ereignisse habe ich auch noch im Kopf. Was ich aber 1995 selbst so getrieben habe, das weiß ich nicht mehr genau. Ich kann mich nur noch daran erinnern, dass ich ständig auf irgendwelchen Konzerten unterwegs war und Musik hoch und runter gehört habe. Das war zwar cool, aber trotzdem hat sich mein Leben auch irgendwie langweilig angefühlt – jedenfalls bis zu dem Zeitpunkt, als ich Peter und die Jungs kennengelernt habe. Es war wirklich toll, endlich Menschen gefunden zu haben, die genauso besessen waren von Musik wie ich. Mit einem Mal war auch meine Langeweile weg und ich hatte das Gefühl, dass mein Leben wieder einen Inhalt hat.

Jonas:

Wie habt ihr alle damals zueinander gefunden?

Peter:

Es gab da einen Kumpel, dem ich irgendwann einmal erzählt hatte, dass ich gerne wieder mit ein paar Leuten Musik machen würde. Er sagte sofort „Ich kenn’ da wen!“ und hat mich wenig später zu einer Bandprobe von The Beatsteaks mitgenommen – im Bandnamen gab es ganz am Anfang noch ein „The“. Dadurch habe ich Bernd Kurtzke sowie Stefan Hircher und Alexander Rosswaag kennengelernt – die beiden Gründungsmitglieder, die heute nicht mehr mit an Bord sind. Von diesem Tag an haben wir Vier zusammen Musik gemacht, damals noch in einem winzigen Keller, dessen Wände überall mit Filz behangen waren. Das hat von der ersten Minute an riesigen Spaß gemacht und war absolut aufregend.

Über einen Arbeitskollegen habe ich ein paar Wochen später Arnim kennengelernt. Wir waren uns irgendwie sofort grün und haben uns richtig gut verstanden. Auch Arnim ist einfach mal mit zur Bandprobe gekommen und war ab diesem Moment mit dabei. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt waren wir allerdings schon in einen wesentlich schöneren und größeren Probenraum umgezogen. Diesem neuen Probenraum, der in der Schönhauser Allee 48/49 lag, haben wir zwei Jahre später auch den Titel unseres ersten Albums gewidmet.

Jonas:

Wie das im Leben so ist: Wenn man erst einmal irgendwo festhängt…

Peter (lacht):

… dann hängt man dort fest. Die Band war für uns alle wie eine schöne Insel, auf der man den Alltag vergessen und abschalten konnte – eben genau das, was ein gutes Hobby ermöglichen sollte. Probe war jeden Dienstag und Donnerstag um 17 Uhr. Dann war Freiflug angesagt.

Diese Nachmittage Mitte der 90er fand ich immer total schön. Dabei hatten sie für uns gar keinen größeren Sinn. Wir haben es einfach nur genossen, gemeinsam laute Musik zu machen. An so etwas wie Live-Auftritte oder Platten aufnehmen hat damals noch absolut keiner von uns gedacht.

Lustigerweise erinnert mich dieses Gebäude, in dem wir uns gerade befinden, an unseren damaligen Probenraum. Die Platten draußen an der Wand sehen noch verdächtig nach Asbest aus – der Giftstoff, der früher überall zum Dämmen benutzt wurde. Ich weiß noch, wie ich mit Bernd in der Schönhauser Allee nichtsahnend etliche Asbest-Platten zersägt habe, um die Wände zu isolieren

Jonas:

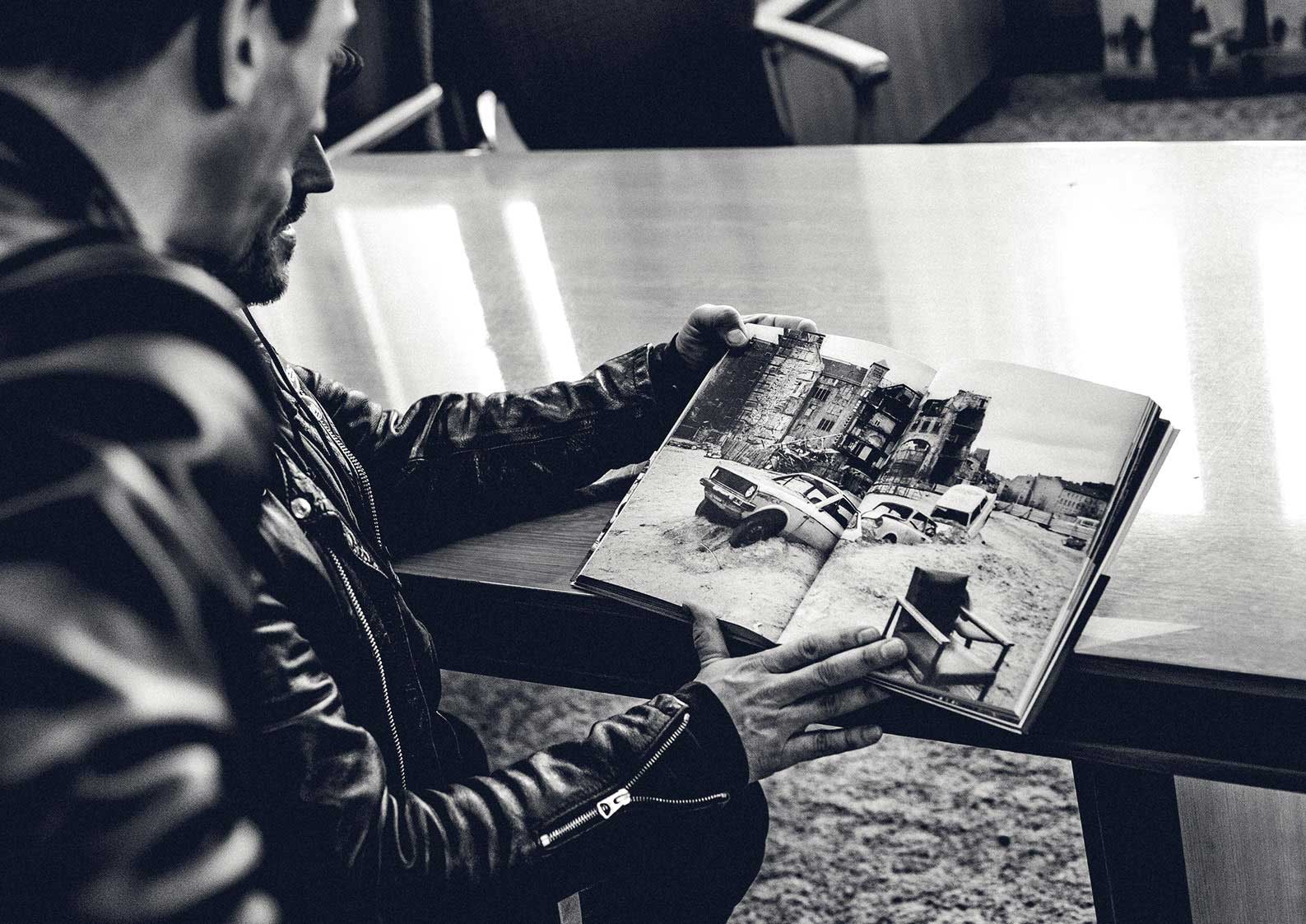

Leider haben wir selbst das Berlin der 90er Jahre nicht erleben können. Gott sei Dank gibt es aber Dokumentationen wie etwa das Buch „Berlin Wonderland – Wild Years Revisited“, das uns im Ansatz ein Bild von dieser Zeit vermitteln kann – und das uns in etwa zeigt, aus welchem kreativen Biotop heraus eure Musik damals entstanden ist. Kann man eurer Meinung nach das Berlin der 90er tatsächlich als Wunderland bezeichnen?

Es gab ständig irgendwelche Konzerte in Berlin. Das ist zwar heute nicht anders, aber damals waren die Leute musikalisch total ausgehungert. Musiker wie Paul McCartney hatte ja im Osten nie jemand gesehen.

Arnim:

Ja, das war’s definitiv. Man muss wissen: Vier Jahrzehnte lang haben sich die beiden Teile Berlins völlig unterschiedlich entwickelt. Als plötzlich die Mauer weg war, strömten die Menschen in beide Richtungen. Nein, eigentlich strömten sie zuerst einmal nur in eine Richtung: in den Westen. Und so gab es mit einem Mal im Ostteil der Stadt unglaublich viel Platz. Überall entstanden Freiräume: Immer wieder wurden Gebäude besetzt, an den unterschiedlichsten Orten wurden Clubs eröffnet. Oder unerlaubte Partys veranstaltet. So hatte Berlin Anfang, Mitte der 90er etwas von einer verlassenen Stadt, obwohl es hier eigentlich damals schon total voll war.

Auch aus musikalischer Sicht hat sich in jener Zeit wahnsinnig viel bewegt. Die Electro- und Alternative-Szene, die sich hier in den 90ern entwickelt hat, brachte Bands hervor, die plötzlich an der Spitze der Charts standen.

Ohnehin gab es ständig irgendwelche Konzerte in Berlin. Das ist zwar heute nicht anders, aber damals waren die Leute musikalisch total ausgehungert. Musiker wie Paul McCartney hatte ja im Osten nie jemand gesehen. Auf einmal aber konnte man sich persönlich ein Konzert von ihm ansehen. Am nächsten Abend konnte man dann bei Westbam im Tresor sein und wieder einen Abend später die Beasty Boys im Loft anhören – einfach nur, weil es da war, weil es möglich war.

Jonas:

Vermisst ihr diese Zeit?

Arnim:

Nein, vermissen wäre zu viel gesagt. Wir haben einfach eine schöne Zeit erlebt, eine Zeit des totalen Aufbruchs. Daher schaue ich gerne zurück.

Peter:

Berlin war Mitte der 90er nicht weniger als ein Abenteuerspielplatz für Erwachsene.

Arnim:

Ich war damals noch gar nicht richtig erwachsen, wir alle nicht. Wir waren eher Kiddies.

Jonas:

Aber heute bist du erwachsen…

Arnim:

Ja, spätestens ab dem Moment, in dem man Vater wird, ist man endgültig erwachsen. Sollte man jedenfalls. (Arnim lächelt)

Jonas:

Eure Bandgeschichte ist eigentlich in erster Linie eine Freundegeschichte. Nun können Freunde ja vor allem durch eine gemeinsame Haltung verbunden sein, durch einen gemeinsamen Humor oder durch eine gemeinsame Idee von Musik. Was genau ist es, dass euch in eurer Freundschaft verbindet?

Arnim:

All das, was du gerade gesagt hast, und noch vieles, vieles mehr!

Peter:

Wenn ich mich für eines der genannten Dinge entscheiden müsste, wäre es eindeutig der Humor – denn alles andere basiert darauf in unserer Freundschaft.

Jonas:

War euch bei eurem allerersten Aufeinandertreffen klar: Diese Leute werde ich in meinem Leben nicht mehr los?

Arnim:

So radikal würde ich es nicht beschreiben. Ich würde eher sagen: Es war von Anfang an klar, dass man sich jetzt öfter trifft. Wir alle hatten ja nie überhöhte Vorstellungen, sondern sehr gesunde Ambitionen. So haben wir uns einfach immer nur gewünscht, dass wir bei der nächsten Probe genauso viel Spaß haben wie bei der davor. Und als wir zum ersten Mal im SO36 spielen durften, haben wir uns gewünscht dass wir noch einmal im SO36 spielen dürfen. Mehr nicht. Obwohl wir alle sehr, sehr unterschiedliche Charaktäre sind, hatten wir immer eine ziemlich klare Haltung dazu, was die Beatsteaks sind und wie sie funktionieren.

Jonas:

Bezieht sich das auch auf die Musik?

Arnim:

Nein. Was die Musik angeht, die wir selbst hören, waren wir damals schon absolut verschieden. Und das ist auch heute noch so.

Peter:

Was die Musik angeht, die wir selbst machen, ist es so, dass es immer gemeinsame Schnittpunkte gibt, bei denen alle sagen können: Das ist super.

Dass unsere Musik trotzdem so breit gefächert ist, liegt unter anderem daran, dass sich in der Band in der Regel immer irgendwelche Zweier- oder Dreiergrüppchen bilden, die etwas gut finden oder eine bestimmte Idee haben. Wenn man das als Einzelner anders sieht und demokratisch überstimmt wird, muss man damit klarkommen – im schlimmsten Fall. (Peter lacht)

Jonas:

Trotzdem ist es euch in den 20 Jahren gelungen, einen unverwechselbaren Sound zu entwickeln, den man immer mit den Beatsteaks in Verbindung bringt, sobald man ihn wahrnimmt.

Peter (lächelt):

Es ist wirklich schön zu hören, dass das von außen so empfunden wird. Man legt es ja nicht gezielt darauf an, so einen Sound zu erschaffen. Das ist einfach den Personen geschuldet, die bei den Beatsteaks Musik machen, und ergibt sich eher automatisch.

Arnim:

Und es ist eine Konsequenz daraus, dass wir immer schon darauf geachtet haben, dass wir uns nicht wiederholen. Dieser Weg ist definitiv der schwierigere, da man innerhalb der Band nicht immer alles gleich sieht. Trotzdem würde ich mal behaupten, dass wir es ganz gut hinbekommen haben, uns über die Jahre zu entwickeln und dabei immer gerade die Musik zu machen, die wir in in dem Moment lieben.

Das hat übrigens auch die Arbeit an unserem neuen Album „23 Singles“ so interessant gemacht, weil wir uns dadurch intensiv mit unserer eigenen Geschichte befassen konnten. Auf dieser Platte präsentieren sich neben zwei brandneuen Songs insgesamt 21 Beatsteaks-Klassiker, die wir neu gemastert haben. Als wir die Tracks zusammengestellt haben, hat es sich angefühlt, als würden wir ein altes Fotoalbum aufschlagen und feststellen, wie sich unsere Frisuren und Klamotten über die Jahre verändert haben.

Jonas:

Ganz am Anfang eurer Bandgeschichte habt ihr stellenweise noch auf Deutsch gesungen. Warum habt ihr euch damals letztendlich dazu entschlossen, nur noch englische Texte zu schreiben?

Für uns war die englische Sprache eine schöne Insel, auf die man sich aus dem Alltag flüchten konnte, auf die man sich aus dem Deutschen flüchten konnte.

Arnim:

Das war eine ganz bewusste Entscheidung. Wir fanden es irgendwie nicht so interessant, in unserer Muttersprache zu singen. Daher gab es bei uns insgesamt auch nur zwei, drei Ausflüge ins Deutsche.

Außerdem wollte ich persönlich immer Englisch singen und habe auch bis auf Die Ärzte keine deutsche Musik gehört. Für mich als Sänger war Englisch damals schon die Sprache, in der ich mich ausdrücken wollte.

Ganz abgesehen davon wollten wir auch nie Interviews geben, in denen wir uns hätten zu unseren Texten erklären müssen. Dazu hat uns das, was wir damals so von deutschsprachigen Bands in der Presse lesen konnten, viel zu sehr abgeschreckt. Auf Fragen wie „Was meinst du denn mit dieser Textstelle?“ oder „Was willst du denn damit sagen?“ hatten wir einfach keinen Bock. Mit englischen Texten konnten wir dieses Problem mehr oder weniger umgehen.

Peter:

Wie die Band war für uns auch die englische Sprache eine schöne Insel, auf die man sich aus dem Alltag flüchten konnte, auf die man sich aus dem Deutschen flüchten konnte. Außerdem haben wir uns einfach als eine coole Band verstanden. Und zu einer coolen Band gehörte damals auch, in einer Sprache zu singen, die mehr Freiheiten eröffnete, als es die bisherigen Hörgewohnheiten so ermöglichen konnten.

Jonas:

Dass ihr eine coole Band seid, haben irgendwann auch andere Menschen bemerkt. So haben sich in den 20 Jahren Beatsteaks unzählige Preise und Auszeichnungen angesammelt. Erinnert ihr euch an ganz bestimmte Ereignisse, die prägend waren für euren Erfolg und die die Weichen in die entscheidende Richtung gestellt haben?

Peter:

Ich erinnere mich weniger an konkrete Einzelereignisse, dafür aber an etliche geile Momente zwischendurch, die wir erleben durften. Ich weiß noch, wie wir einmal im SO36 gespielt haben und plötzlich neben den Jungs von Faith No More standen, die an dem Abend ebenfalls aufgetreten sind. Chuck Mosley, der Sänger, unterhielt sich mit uns – so von Musiker zu Musiker. Das haben wir zuerst gar nicht kapiert, weil wir alle riesige Faith No More-Fans waren und uns dadurch in erster Linie auch nicht als Musiker verstanden haben. In diesem Moment haben wir gemerkt, dass uns unsere Musik ja vielleicht auch die Möglichkeit bieten könnte, erfolgreich zu sein und damit unseren Lebensunterhalt zu bestreiten.

Arnim:

Für mich gab es so einen prägenden Moment, als ich unsere Musik zum ersten Mal im Radio gehört habe. Das war so krass, ich konnte es kaum glauben: Hatte die Radiomoderatorin wirklich gerade unseren Namen gesagt? Da läuft tatsächlich jetzt unser Song, so ganz selbstverständlich nach einem Kracher wie „Hip Hop Hooray“ von Naughty by Nature? Das war absolut strange und schön zugleich – und dabei genauso überwältigend wie das erste Konzert, das wir gespielt haben, oder der Tag, an dem wir zum ersten Mal mit dem legendären Musikproduzent Moses Schneider zusammenarbeiten durften.

Jonas:

Mit Moses habt ihr damals die Platte „Smack Smash“ produziert – euer erstes Erfolgsalbum, wie es so schön heißt.

Arnim:

Das stimmt. Zwar waren für uns die beiden Alben davor auch schon Erfolgsalben, aber „Smack Smash“ war die Platte, auf der wir plötzlich zu uns und unserem ganz eigenen Beatsteaks-Stil gefunden haben: Hatten wir vor diesem Album noch stellenweise gewollt nach anderen Bands geklungen, haben wir spätestens seit „Smack Smash“ unser eigenens Süppchen gekocht.

Jonas:

Ihr seid in eurem musikalischen Leben einer Reihe außergewöhnlicher Künstler begegnet und habt an den unterschiedlichsten Stellen mit diesen Persönlichkeiten zusammengearbeitet. Gab es in den 20 Jahren bestimmte Menschen, die euch ganz besonders beeindruckt haben?

Bands wie „Die Toten Hosen“ oder „Die Ärzte“ haben uns vorgelebt, wie man Konzerthallen füllen kann und trotzdem kein Arschloch sein muss.

Arnim:

Ja, die gibt es. Pierre Baigorry alias Peter Fox zum Beispiel. Pierre ist ein Mensch, den wir alle außerordentlich schätzen – und den wir bewundern für seine ehrliche und gerade Haltung. Es ist total geil und macht wahnsinnig viel Spaß, mit so einem Typen mal einen Tag lang Musik zu machen.

Darüber hinaus würde ich sagen, dass uns generell alle Musiker beeindruckt haben, mit denen wir als Vorband auf Tour gehen durften. Von Bands wie den Toten Hosen oder Die Ärzte haben wir wirklich viel gelernt.

Jonas:

Zum Beispiel?

Arnim:

Zum Beispiel wie man sich als Band korrekt gegenüber einer Vorband verhält.

Peter:

Und wie man sich überhaupt verhält. Diese Bands haben uns vorgelebt, wie man Konzerthallen füllen kann und trotzdem kein Arschloch sein muss.

Arnim:

Oder auch: Wo man Geld verdient und wo man besser kein Geld verdient.

Peter:

Wir haben vor allem sehr viel darüber gelernt, was man nicht machen sollte. Das ist für eine Band fast noch wichtiger als zu wissen, was man machen muss, denn das sagt dir dein Bauch schon ganz alleine. Und alles Weitere ist Erfahrung.

Jonas:

Ich springe nochmal in das Jahr 1995 zurück. Damals wurde die DVD vorgestellt, Windows 95 kam auf den Markt und „Multimedia“ war das Wort des Jahres. Rückblickend wirken diese Ereignisse wie eine Prophezeihung, wenn man sich vor Augen führt, dass in der heutigen Medienlandschaft eigentlich kein Musiker mehr ohne Website, Facebook-Page oder YouTube-Channel überleben kann. Empfindet ihr diese Entwicklung – bezogen auf die Beatsteaks – eher als Fluch oder als Segen?

Arnim:

Wir haben das in erster Linie als eine interessante Reise empfunden. Wir kommen ja aus einer Zeit, in der noch Platten verkauft wurden und diese Plattenverkäufe auch extrem wichtig waren. Damals gab es das Internet noch nicht in der breiten Masse und Social Media Plattformen wie Facebook oder YouTube waren noch gar nicht erfunden.

Das Gute daran ist, dass wir unsere eigene kleine Burg fertig bauen konnten, bevor dieser ganze Wahnsinn losgegangen ist. Daher stehen wir auch nicht unter dem Druck, dem heute Bands ausgesetzt sind, wenn sie sich gründen und erfolgreich sein wollen. Wir haben das große Glück, nicht alle Medien bespielen zu müssen, sondern uns aussuchen zu können, welche Plattform wir nutzen möchten, um unsere Botschaften zu kommunizieren.

Ich möchte auch in der heutigen Zeit nicht nochmal anfangen müssen. Allein die Tatsache, dass im Netz ständig jeder alles kommentiert und kritisiert, finde ich total krass. Dafür braucht man als junge Band von Anfang an eine dicke Haut. Und die hatte ich persönlich vor 20 Jahren nicht.

Natürlich wurde auch damals schon hinter unserem Rücken kritisiert und gelästert, aber das haben wir nicht mitbekommen und schon gar nicht irgendwo lesen müssen. Wenn man heute in der Öffentlichkeit steht, kann man sich direkt und unmittelbar ein Bild davon machen, was bestimmte Gruppen von Menschen über einen denken. Das empfinde ich als sehr ungesund, denn es besteht die Gefahr, dass man ständig darüber nachdenkt, ob das, was man tut, anderen gefällt oder nicht.

Heute gibt es ein Überangebot an Meinungen, das einen dazu zwingt, sich genau zu überlegen, wo man sich wie darstellt.

Peter:

Vor 20 Jahren war alles einfach übersichtlicher. Damals hat man einfach einer Zeitschrift ein Interview gegeben, das man anschließend überall als Referenz aufführen konnte. Heute gibt es ein Überangebot an Meinungen, dass einen dazu zwingt, sich genau überlegen zu müssen, wo man sich wie darstellt. Das finde ich extrem anstrengend.

Jonas:

A propos Internet: Auf eurer Website habt ihr eine interaktive Fototapete eingerichtet, auf der man Erinnerungsfotos von Momenten aus 20 Jahren Beatsteaks posten kann – eine schöne Idee, sich gemeinsam mit den Fans an die Zeit von 1995 bis heute zu erinnern.

Peter:

Ja, das ist eine richtig geile Sache. Wir haben unsere Website davor immer nur als Newskanal benutzt, über den wir unsere Fans angesprochen haben. Mit der Photowall haben wir diesen Mechanismus umgedreht. Das ist ein gutes Beispiel dafür, dass das Internet auch unendlich viele Vorteile bietet.

Jonas:

Es hilft einfach beim Erinnern.

Arnim:

Ja, in unserem Fall durch die vielen alten Fotos. Mir persönlich würde es aber schon reichen, mich lediglich anhand von Musik an die Vergangenheit zu erinnern. Und damit meine ich nicht nur unsere eigene Musik, sondern auch die, die ich selbst im Laufe meines Lebens so gehört habe. Wenn ich heute auf einen Song stoße, der mich früher mal berührt hat, ist die Erinnerung sofort wieder da.

Als du eben gefragt hast, was uns zum Jahr 1995 einfällt, habe ich daher auch zu allererst an die Musik aus dieser Zeit gedacht. Damals hat beispielsweise Oasis das Album „(What’s the story) Morning Glory?“ herausgebracht – das hat mich absolut umgehauen. Wenn ich mir heute die Erinnerung an eine bestimmte Zeit ins Gedächtnis rufen will, muss ich mir nur wieder die Musik anhören, die mich damals umgehauen hat, und schon sind alle Bilder dazu in meinem Kopf.

Jonas:

Wenn unser kleiner Jahresrückblick vollständig sein soll, müssen wir auch darüber sprechen, dass 1995 das Jahr des Terrors war: Der Bombenanschlag in Oklahoma, der Giftgasanschlag in der Tokioter Ubahn, das Massaker an den bosnischen Muslimen in Srebrenica und der Brandanschlag auf die Synagoge in Lübeck sind Ereignisse, die uns noch heute in grausiger Erinnerung sind. Wenn man sich vor Augen führt, dass drei Jahre vorher bereits Asylunterkünfte in Rostock-Lichtenhagen in Brand gesetzt wurden und im Deutschland des Jahres 2015 immer noch beschämende Bilder von Fremdenfeindlichkeit im TV zu sehen sind, verliert man da die Hoffnung, dass der Mensch sich ändern kann?

Arnim:

Ganz grundsätzlich würde ich nicht sagen, dass sich in den letzten 20 Jahren nichts verändert hat. Nur springt diese Entwicklung leider immer wieder zurück. Ich habe das Gefühl, dass immer dann, wenn es den Leuten in Deutschland zu gut geht, die Dinge wieder in diese bestimmte Ecke zurückschwappen.

Wer weiß schon, was diese Leute umtreibt. Vielleicht ist es Frustration oder das Gefühl fehlender Zugehörigkeit. Auf jeden Fall scheint ihnen die Menschlichkeit abhanden gekommen zu sein.

Peter:

Meiner Meinung nach machen diese Leute, um die es da geht, aber nur einen kleinen Prozentsatz der großen Masse aus. Leider ist es nur immer dieser laute und dumme Teil der Bevölkerung, den man dann im Fernsehen sieht und an dem man sich aufhängt. So wird ständig eine besonders hässliche Seite der Gesellschaft gezeigt, die latent immer vorhanden ist, aber nicht für die Mehrheit steht.

Wer weiß schon, was diese Leute umtreibt. Vielleicht ist es Frustration oder das Gefühl fehlender Zugehörigkeit. Auf jeden Fall scheint ihnen die Menschlichkeit abhanden gekommen zu sein: Sie sind nicht in der Lage, sich in einen anderen Menschen hineinversetzen zu können, dem es schlechter geht als ihnen selbst. Wahrscheinlich haben sie nie gelernt, eine gewisse Empathie zu entwickeln. Das tut mir einfach leid. Die Tatsache, dass sich solche Ereignisse immer wiederholen, zeigt mir, dass es Dinge gibt, die ganz tief in einigen Menschen schlummern und jahrelang nicht geweckt werden, bis sie irgendwann ausbrechen.

Lustigerweise handelt es sich dabei immer um genau die Leute, die sich sonst nie um andere kümmern. Wenn aber plötzlich Menschen ins Land kommen, die wirklich Hilfe brauchen, schreien sie auf einmal: „Und was ist mit unseren Obdachlosen? Sollen wir uns nicht zuerst um die kümmern?“ Dabei hätten sie sich doch all die Jahre davor um die Obdachlosen hier kümmern können, warum fällt ihnen das gerade jetzt ein? Es wird ja niemandem etwas weggenommen. Wenn ich so etwas sehe und höre, ist mir das sehr peinlich. Und ich schäme mich dafür, dass Leute, die hier herkommen, diese hässliche Seite unserer Gesellschaft erleben müssen.

Jonas:

Ihr habt für euch in den letzten 20 Jahren einen ganz persönlichen Weg gefunden, auf diese und andere Missstände aufmerksam zu machen und dagegen zu protestieren. Ihr engagiert euch aktiv in etlichen sozialen Projekten und gebt Benefizkonzerte wie beispielsweise jetzt im September in Dresden, wodurch ihr Organisationen wie „Dresden für alle“ oder „Sächsischer Flüchtlingsrat“ unter die Arme greift. Sollte dieses Engagement eine Pflicht für jeden sein, der in der Öffentlichkeit steht? Oder sollte es generell die Pflicht eines jeden Menschen, eines jeden Bürgers sein?

Arnim:

Wir tun einfach das, was wir tun können. Genauso wie ein Bäcker 50 Brötchen backen und an Flüchtlinge spenden kann, können wir Musik machen, Benefizkonzerte spielen und Geld sammeln. Wenn jeder tut, was er kann, dann passiert eine ganze Menge.

Peter:

Noch in unserer Anfangszeit wollten wir nie eine politische Band sein – was auch immer das heißt. Wir wollten uns einfach aus allem heraushalten und nicht die Speerspitze für die Argumentation von irgendwem für irgendetwas sein. So war diese Band für uns selbst auch immer ein Abschalter und Ausschalter von Problemen jeglicher Art.

Irgendwann reicht das aber nicht mehr, man merkt: Das ist zu wenig. Früher dachte ich immer: Wen interessiert denn meine persönliche Meinung? Heute ist mir bewusst, dass ich die Möglichkeit habe, jemand anderen zum Nachdenken anzustoßen. Der- oder diejenige muss ja nicht zwangsläufig meiner oder unserer Meinung sein. Aber ich kann wenigstens versuchen, etwas in der Person auszulösen.

Arnim:

Natürlich beschäftigt mich auch privat das politische Leben auf der Welt – wie hoffentlich jeden anderen auch. Aber wenn ich weiß, dass es Leute gibt, die mich beobachten und sich ein Beispiel an mir nehmen, kann ich ja immer wieder das Buch aufschlagen und sagen: Schaut doch mal genau hin!

Wenn man in der Öffentlichkeit steht, muss man sich halt finden und entscheiden, wie man sich positioniert. Aber irgendwann ist auch mal gut mit Nachdenken. Dann geht es im Grunde genommen um nichts anderes, als einfach die 50 Brötchen zu spenden oder das Benefizkonzert zu spielen. Punkt.

Jonas:

Auf dem Cover eures neuen Albums ist ein kleiner Junge zu sehen, der die Arme die Luft streckt und beide Fäuste ballt, als sei er in einem Boxkampf. Er wirkt wie ein kleiner mutiger Rebell, der auf eine freche, aber sympathische Art und Weise aufsteht, um sich zu wehren. Wie kam es zu dem Foto?

Arnim:

Wir hatten den großen Wunsch, nicht selbst auf dem Cover abgebildet zu sein. Durch Zufall sind wir auf das Bild eines New Yorker Fotografen gestoßen, das einen kleinen Jungen zeigt, der mit einer selbst gebastelten Gitarre vor der Kamera post. Wir fanden die Aussage des Fotos irgendwie cool und haben es einer befreundeten Fotografin gezeigt. Sie sagte sofort: „Mir fällt da einer ein, das ist genau euer Mann. Er heißt Vito und ist mit meiner Tochter in derselben Kita.“ Und so kam es zu dem Cover.

Jonas:

Dieses Foto schafft es, die insgesamt 20 Jahre Beatsteaks mit einer einzigen Pose zusammenzufassen und auf den Punkt zu bringen.

Jeder Mensch kommt ja immer wieder mal in eine Situation, in der ihm der Mut fehlt. Das ist bei mir nicht anders.

Arnim:

Stimmt, exakt darum ging es uns auch. Wir wollten genau so ein Gesicht finden – und Vito war einfach perfekt. Als ich den kleinen Mann am Tag des Shootings kennengelernt habe, wusste ich in der ersten Sekunde: Alles klar, dieser Typ macht das. Der ist wirklich cool.

Jonas:

Seid ihr der Meinung, dass mehr Menschen auf der Welt ein wenig von diesem kleinen Jungen in sich tragen sollten?

Arnim:

Hmm, ich weiß es nicht. Jeder Mensch kommt ja immer wieder mal in eine Situation, in der ihm der Mut fehlt. Das ist bei mir nicht anders. Aber wenn ich oder die Menschen, die ich liebe, mal wieder in solch eine Lage kommen sollten, wäre es schön zu wissen, dass plötzlich jemand neben uns stünde, der so ist wie dieser kleine Junge.

Arnim Teutoburg-Weiß und Peter Baumann sind Mitglieder der Band Beatsteaks und leben in Berlin.

Tobias Auner

Interview — Tobias Auner

Ein guter Freund

Tobias Auner glaubt, dass in jedem Mensch das Bedürfnis steckt zu tanzen. Wir haben den jungen Tänzer und Choreograph aus München für eine kleine Videoproduktion gewonnen und reden nun mit ihm über Konkurrenzkämpfe, Selbstzweifel und Vorurteile. Und natürlich über das Tanzen.

29. November 2015 — MYP No. 19 »Mein Protest« — Interview: Jonas Meyer, Fotos: Maximilian König

Ein Burgerladen in Friedrichshain an einem späten Sonntagabend. Viel los ist nicht mehr, die meisten Gäste sitzen längst zuhause vor dem Tatort und verdauen. Gut für uns, denn so gibt es keine Warteschlange, für die dieser Ort berühmt und auch berüchtigt ist. Also rein in die gute Stube!

Wir nehmen an einem kleinen Tisch neben der Bar Platz, schalten unsere Telefone aus und arbeiten uns durch die endlos lange Speisekarte. Was soll man nur bestellen? Erstmal ein großes, kühles Bier für jeden, das hilft bei der Entscheidungsfindung. Irgendwie fühlen wir uns wie benebelt, denn die Luft riecht nach einer Mischung aus Grill-, Brat- und Fritteusenfett. Auf einigen Tischen liegen die sterblichen Überreste von Bacon, Patties und geschmolzenem Käse, Mayo- und Ketchupspender laufen auf Reserve. Spuren, die erahnen lassen, welche Orgie aus Fleisch, Fritten und Gemüsedeko sich hier heute wieder abgespielt haben muss.

So etwas wollen wir jetzt auch, schließlich bewegen wir uns gerade irgendwo zwischen Hunger und Erschöpfung. Außerdem gibt’s was zu feiern, denn für uns ist der heutige Abend der krönende Abschluss eines langen und intensiven Wochenendes. Gemeinsam mit dem Tänzer Tobias Auner haben wir in den letzten Tagen in und um Berlin ein Musikvideo gedreht, das auf dem Song „Warm Dark Night“ der skandinavischen Band DNKL basiert. Auf den 19-jährigen Münchener sind wir vor etwa einem halben Jahr aufmerksam geworden, als wir unser Interview mit dem Musiker Martin Brugger alias Occupanther vorbereitet haben. In dessen Musikvideo zum gleichnamigen Song „Chimera“ wurde Tobias für die Hauptrolle besetzt und tanzt dort auf eine Art und Weise, wie wir sie bisher nicht kannten. Resolut, ja sogar hart sind seine Bewegungen, dabei aber gleichzeitig harmonisch und absolut präzise. Seine Hände scheinen in einem Moment wie ein Fallbeil die Luft zu spalten, nur um sie im nächsten Moment wieder glatt zu streichen. Und wenn man wegen der Geschwindigkeit und Turbulenz seiner Bewegungen gerade glaubt, er würde fliegen, erlebt man einen Augenblick später, wie sein Körper langsam und kontrolliert zu Boden schwebt.

Doch zurück ins Hier und Jetzt. Tanzen macht hungrig. Und Filme drehen auch. Auf der Speisekarte haben wir endlich unsere Burger- und Pommesfavoriten ausgemacht. Bestellt haben wir schnell, jetzt heißt es nur noch warten. Aber Vorfreude ist ja bekanntlich die schönste Freude. Vor allem, wenn man sie mit jemandem teilen kann.

Jonas:

Bevor du für unseren Videodreh nach Berlin gekommen bist, warst du zwei Wochen lang in Polen unterwegs. Was hast du dort gemacht?

Tobias:

In Warschau habe ich an einem sogenannten Dance Camp teilgenommen. Das ist eine Veranstaltung, bei der hunderte Leute aus der Tanz-Community zusammenkommen, um in intensiven Workshops Tanzunterricht zu erhalten. Das Besondere dabei ist, dass die Kurse von sehr bekannten Tanzlehrern aus der ganzen Welt geleitet werden. So ein Dance Camp kann mehrere Tage oder sogar Wochen dauern und ist in der Regel recht erschwinglich. Für die zwei Wochen in Polen habe ich etwa 700 Euro gezahlt, inklusive Unterkunft und Verpflegung.

Jonas:

Was genau wird einem dort beigebracht?

Tobias:

In einem Dance Camp lernt man verschiedene Choreographien. Das sind vereinfacht gesagt spezielle Bewegungsabfolgen, die eine Person – der Choreograph – zu einem bestimmten Song entwickelt und festgelegt hat. Eine gute Choreographie hat für die Tanz-Community eine ähnliche Bedeutung wie ein sehr bekanntes Lied für die Allgemeinheit: Wenn man einen bekannten Song im Radio hört und er gute Stimmung erzeugt, singt man automatisch mit. Und wenn jemand in der Tanz-Szene ein tolles Video mit einer guten Choreographie veröffentlicht, wollen die Leute unbedingt lernen, das zu tanzen. Im Dance Camp in Polen hat man am Tag gleich sieben HipHop-Choreographien gelernt: sieben Unterrichtseinheiten á 1,5 Stunden – das war total intensiv.

Jonas:

Kannst du dich noch erinnern, wann du zum ersten Mal in deinem Leben mit Tanzen in Berührung gekommen bist?

Tobias:

Ja, das weiß ich sogar ganz genau. Das war im August 2010, als der Film „Step Up 3D“ herausgekommen ist – ich habe das Gefühl, als wäre es erst gestern gewesen. Damals war ich 15 Jahre alt und wollte zusammen mit zwei Freunden ins Kino gehen. Und da gerade nichts Besseres lief, haben wir uns eben für diesen Film entschieden. Wir haben uns nicht viel dabei gedacht und hatten dementsprechend auch überhaupt keine Erwartungen. Aber als der Film vorbei war, kamen wir alle total begeistert aus dem Kino – was wir da gesehen hatten, wollte uns nicht mehr aus dem Kopf gehen: In knapp zwei Stunden haben wir auf der Leinwand erlebt, was Tanzen bedeuten kann, welche Möglichkeiten es einem Menschen eröffnet und welche besonderen Freundschaften es hervorbringt. Einfach gesagt: Wir haben durch den Film erlebt, was für eine wunderschöne Sache das Tanzen ist.

Jonas:

Was genau meinst du damit, wenn du sagst, dass Tanzen besondere Freundschaften hervorbringt? Zu diesem Zeitpunkt war das Ganze für dich ja „nur“ ein Kinofilm und damit Fiktion.

Tobias:

Unabhängig davon, ob der Film Fiktion war oder nicht, hatte ich den Eindruck, dass Tanzen ganz allgemein eine Verbindung zwischen Menschen aufbauen kann. Ich glaube, das ist auch der Hauptgrund, warum mich dieser Film so fasziniert und Tag und Nacht begleitet hat.

Meinen beiden Freunden ging es ähnlich. Ein paar Tage später sagte einer von ihnen: „Lasst uns doch einfach mal zu einer Tanzschule gehen und das Ganze ausprobieren! Es gibt ja niemanden, der uns daran hindert.“ Also haben wir – erstmal zu zweit – tatsächlich bei einer Tanzschule vorbeigeschaut. Allerdings waren wir an dem Tag viel zu früh dort. Niemand war zu sehen, es war noch kein Betrieb. Und so kamen wir uns etwas komisch vor: Wir waren total eingeschüchtert und wussten nicht, was wir tun sollten.

Irgendwann haben wir eine Tür geöffnet und standen plötzlich in einem Raum, in dem 20 Leute auf dem Boden saßen. Alle Gesichter starrten in unsere Richtung, was für eine unangenehme Situation! Wir sind sofort rausgerannt, das Ganze war uns total peinlich. Erst drei Tage später hatten wir wieder den Mut, erneut dort vorbeizuschauen. Diesmal waren wir zu dritt – und haben uns vorher zur Sicherheit telefonisch angekündigt. (Tobias grinst)

Jonas:

So kamst du zu deiner ersten Tanzstunde.

Tobias:

Ja. Und ich war von der ersten Minute an geflasht. Wenn ich heute daran denke, wie ich mich damals gefühlt habe, bekomme ich immer noch eine Gänsehaut. Das war ein unbeschreibliches Gefühl! Als ich nach der ersten Tanzstunde zuhause angekommen bin, habe ich mich sofort in meinem Zimmer eingesperrt, die Musik aufgedreht und weitergetanzt. Ich habe die Bewegungen geübt, die ich gerade gelernt hatte, und im Internet recherchiert, was man noch so alles machen kann. Von diesem Moment an gab es in meinem Leben nichts Anderes mehr.

Jonas:

Hattest du das Gefühl, deinen Körper plötzlich auf eine Art und Weise bewegen zu können, die du bis dahin nicht gekannt hast?

Durch das Tanzen hat sich für mich plötzlich ein Weg aufgetan, der mir ermöglicht, mich zu Musik voll und ganz auszudrücken.

Tobias:

Ich würde es etwas anders beschreiben. Ich hatte schon immer eine sehr starke Bindung zu Musik. Durch das Tanzen hat sich für mich plötzlich ein Weg aufgetan, der mir ermöglicht, mich zu Musik voll und ganz auszudrücken.

Jonas:

Wie genau ist deine erste Tanzstunde abgelaufen? Ich kann mir vorstellen, dass einem Anfänger die allererste Bewegung, die er dort machen soll, gar nicht so leicht fällt.

Tobias:

Natürlich nicht. Es gibt keinen Menschen auf der Welt, bei dem so etwas von der ersten Minute an gut aussieht. Das ist einfach unmöglich. Daher haben wir uns auch in den ersten Unterrichtsstunden in den hinteren Reihen versteckt und versucht, in die Sache hineinzufinden. Mit das Wichtigste sind dabei die Lockerungsübungen ganz am Anfang. Wenn man sich bei diesen Bewegungen als Anfänger im Spiegel betrachtet, sagt man sich ganz automatisch: „Junge, zieh den Stock aus dem Arsch!“ Und dann heißt es üben, üben, üben. Man wiederholt so lange die Motorik, bis man irgendwann an einen Punkt kommt, an dem man behaupten kann: Ich kann das jetzt wirklich. Das Entscheidende dabei ist, dass man von der ersten Bewegung an dranbleiben muss. Und man muss davon überzeugt sein, dass es irgenwann etwas wird.

Jonas:

Haben deine Freunde das ebenso wahrgenommen?

Tobias:

Ja, das ging uns allen dreien so.

Jonas:

Was für ein Zufall, dass drei Freunden nichtsahnend ins Kino gehen und im Anschluss jeder von ihnen das gleiche dringende Bedürfnis hat, mit dem Tanzen anzufangen.

Tobias:

Absolut. Wir konnten damals gar nicht mehr still sitzen und waren mit einem Mal so voller Energie und Inspiration, dass wir irgendetwas damit anfangen mussten. Immer wenn wir uns jetzt getroffen haben, haben wir die Bewegungen aus der Tanzschule geübt – zuhause, in der Schule, einfach überall.

Jonas:

In manchen Teilen unserer Gesellschaft wird Tanzen nicht unbedingt als typischer Jungs-Sport angesehen – im Gegensatz zu beispielsweise Fußball oder Handball. Hattest du jemals mit irgendwelchen Vorurteilen zu kämpfen?

Tobias:

Vorurteile gibt es immer, die machen mir nichts aus. Mein Problem ist vielmehr das Unverständnis. Ich empfinde es oft als extrem schwierig, Leuten zu erklären, warum ich überhaupt tanze. Viele schütteln da nur den Kopf. Das hat dazu geführt, dass ich eine Zeit lang dachte, zwei Persönlichkeiten zu haben, ja sogar zwei Leben zu führen: Auf der einen Seite gab es mein „normales“ Leben mit Familie, Schule und Freunden. Und auf der anderen Seite hatte ich mein Leben in der Tanzschule, wo es für mich um etwas so Großes und Faszinierendes ging, das ich außerhalb dieser Welt niemandem begreiflich machen konnte.

Diese Situation hat mich total verwirrt und in einen großen Zwiespalt gebracht. Meine Eltern wollten, dass ich für die Schule lerne. Ich selbst wollte aber nichts anderes als tanzen. Immer wieder fielen Sätze wie „Bist du komplett bescheuert?“ So etwas konnte ich einfach nicht verstehen, denn für mich war und ist Tanzen das Tollste auf der Welt.

Jonas:

Glaubst du, dein Umfeld hätte verständnisvoller reagiert, wenn du in der Jugend des FC Bayern gespielt und jede Minute mit Fußball verbracht hättest?

Tobias:

Ich denke schon – eine Zeit lang habe ich ja sogar auch Fußball gespielt. Ich habe sowieso immer schon viel Sport gemacht. Fußball, Tennis, Badminton – alles habe ich ausprobiert. Aber das Tanzen hat mich einfach in seinen Bann gezogen. Leider ist das nach wie vor für viele Menschen unverständlich.

Jonas:

Wie könnte man es denn erklären, damit es verständlich wird?

Tobias:

Hmm. Ich könnte sagen, dass Tanzen für mich wie ein sehr, sehr enger Freund ist. Wie bei allen engen Freundschaften existiert auch hier eine starke Bindung: Es gibt keine Probleme, man unterstützt sich und fühlt sich seelenverwandt. Wenn es mir mal schlecht geht, wenn ich wütend oder frustriert bin, kann ich mich zu diesem Freund flüchten und alles vergessen. Gleichzeitig weiß ich, dass dieser Freund auch in den schönsten Momenten immer bei mir ist – wenn ich Spaß habe, wenn ich glücklich bin, wenn ich etwas Neues kennenlerne. Kurz gesagt: Ich kann mit ihm alle Erlebnisse teilen, die entscheidend sind für mein Leben. Das macht Tanzen für mich zu einem ganzen Universum.

So individuell wie die Menschen sind, so individuell ist auch ihre Beziehung zum Tanzen.

Jonas:

Empfinden das andere Tänzer in deinem Umfeld ähnlich?

Tobias:

Das ist schwer zu sagen. Tanzen hat für jeden eine andere Bedeutung. Die einen tun es, um dem Alltag zu entfliehen, die anderen tun es, um Erfolg zu haben, wieder andere sehen es schlicht und einfach als ein Hobby und Zeitvertreib an – so individuell wie die Menschen sind, so individuell ist auch ihre Beziehung zum Tanzen.

Jonas:

Ist Tanzen nicht in erster Linie eine Sportart?

Tobias:

Seit einiger Zeit gebe ich auch selbst Tanzunterricht. Wenn die Leute zum ersten Mal in meinem Kurs sitzen, stelle ich immer dieselbe Frage: Was ist Tanzen?

Die simple Antwort lautet: Tanzen ist Bewegung zu Musik. Diese Bewegung ist es, die das Tanzen zum Sport macht. Wie im Fußball gibt es auch hier bestimmte Bewegungsabläufe, die man ständig wiederholt. Während man allerdings beim Fußballspielen irgendwann alle möglichen Bewegungen einstudiert hat, also beispielsweise laufen, dribbeln, schießen oder passen, kann man beim Tanzen immer wieder neue Bewegungsabläufe entdecken und trainieren. Man lernt da nie aus.

Darüber hinaus gibt es beim Tanzen aber noch die Komponente Musik – und die ist es, die es auch zu etwas Künstlerischem macht. Tanzen verbindet Sport also mit Kunst. Mir persönlich gibt es die Möglichkeit, alles Kreative, was in mir steckt und ich ausdrücken will, mit dem zu verknüpfen, was ich sowieso mag, denn seit meiner Kindheit liebe ich Sport über alles.

Jonas:

Zu einer Sportart gehört es auch, sich mit anderen zu messen.

Tobias:

Für mich persönlich ist diese Competition-Sache eher uninteressant. Ich habe bis heute nicht das Bedürfnis, mich zu messen oder sagen zu können, dass ich besser bin als jemand anderes. Ich finde ohnehin, dass es beim Tanzen kein besser oder schlechter gibt, sondern lediglich eigene Meinungen und Empfindungen: Angenommen, man lässt vor tausend Menschen zwei Tänzer auftreten, einen Profi und einen Anfänger. Ich wette, dass es unter den vielen Leuten einige geben wird, die den Anfänger besser finden. Natürlich ist die Mehrheit der Stimmen immer ein Indiz dafür, dass ein Tänzer gut ist. Aber die Minderheit der Stimmen kann nicht bedeuten, dass ein Tänzer schlecht ist. Das ist etwas, was mich am Tanzen bis heute fasziniert und was mich persönlich antreibt.

Jonas:

Trotzdem gibt es gerade in der Tanz-Szene national wie international zahllose Wettbewerbe. Schon im Film „Step Up 3D“ geht es ja im Prinzip nur darum, sich gemeinsam auf einen Wettkampf vorzubereiten und dann dort alles abzuräumen. Hast du das Gefühl, mit deiner Einstellung eher eine Ausnahme in der Tanz-Community zu sein?

Tobias:

Ich würde auf jeden Fall behaupten, dass es dort nicht viele Leute gibt, die ähnlich denken. Für die meisten geht es im Tanzen darum, ihren Erfolg darzustellen, indem sie behaupten können, bei diversen Wettbewerben Erster geworden zu sein. Ich selbst versuche eher, einen individuelleren Weg zu gehen, da ich mich auch als eine individuelle Persönlichkeit begreife. Ich weiß ganz genau, was mir gefällt und was nicht. Und wenn mir etwas nicht gut tut, schiebe ich es von mir weg. Das ist zwar nicht immer einfach, aber ich habe das Gefühl, dass es das Richtige für mich ist.

Jonas:

Da der gesamte Wettkampfbereich für dich eher uninteressant ist: Gibt es andere Erfolgsfaktoren, an denen du deine persönliche Entwicklung festmachen kannst?

Tobias:

Es ist ja nicht so, als hätte es das nie gegeben. Ganz am Anfang meiner Tanzkarriere hatte ich diesbezüglich ein einschneidendes Erlebnis. Auf meiner allerersten Meisterschaft bin ich gleich in der ersten Runde rausgeflogen und durfte in der Konsequenz den ganzen Tag lang von der Bank aus den anderen bei dem zusehen, was ich selbst gerne gemacht hätte. Von diesem Moment an habe ich es gehasst, schlechter zu sein als andere – dieser Hass war lange Zeit lang meine größte Motivation.

Aber irgendwie habe ich es geschafft, mich aus diesem Negativantrieb herauszuarbeiten und mir eine andere Einstellung anzueignen, mit der ich mich wesentlich wohler fühle. Ich glaube, ich habe heute einfach eine andere Sicht auf die Dinge. Zwar existiert in meinem Leben jetzt kein direkter Wettbewerb mehr, aber das heißt ja nicht, dass ich keinen Ehrgeiz mehr habe. Ich trainiere genauso hart wie vorher – lediglich die Ziele, die ich mir stecke, haben nichts mehr mit anderen Leuten zu tun. Nur noch mit mir selbst.

Jonas:

Warst du schon immer so selbstreflektiert? Oder sind daran die zwei Semester Wirtschaftspsychologie schuld, die du studiert hast?

Tobias:

So doof es auch klingt, aber in diesen zwei Semestern habe ich für mich einiges mitnehmen können. Das Studium hat mir die Möglichkeit gegeben, mich extrem mit mir selbst und meiner Umwelt zu beschäftigen. Ich habe dort angefangen, sehr viel darüber nachzudenken, wie ich handle und wie ich gegenüber meinen Mitmenschen auftrete, genauer gesagt wie ich mich präsentiere. Daher würde ich sagen, dass dieses eine Jahr zu den notwendigsten Dingen gehört, die bisher in meinem Leben stattgefunden haben.

So eine intensive Erfahrung zu machen ist allerdings gleichzeitig gut und schlecht. Man lernt zwar einerseits wahnsinnig viel über sich selbst, aber andererseits sollte man sein Leben einfach leben, ohne groß darüber nachzudenken.

Jonas:

Die Tatsache, dass du überhaupt ein Studium angefangen hast, lässt vermuten, dass du später einmal nicht hauptberuflich als Tänzer arbeiten willst.

Wenn ich irgendwann mal sterbe und auf mein Leben zurückschaue, soll Tanzen nicht das Einzige sein, was ich dann vor Augen habe.

Tobias:

Tanzen ist mein Leben, keine Frage. Aber trotzdem möchte ich mein Leben nicht ausschließlich mit Tanzen verbringen. Das heißt, wenn ich irgendwann mal sterbe und auf mein Leben zurückschaue, soll Tanzen nicht das Einzige sein, was ich dann vor Augen habe. Ich möchte vielmehr auf ein Leben blicken, das voller wunderschöner Erfahrungen war und das mir die Chance gegeben hat, sehr viel zu lernen.

Jonas:

Was war der Grund, warum du das Studium bereits nach zwei Semestern abgebrochen hast?

Tobias:

Da ich mir so viel Zeit dafür genommen habe, mich mit mir und meiner Umwelt auseinanderzusetzen, habe ich mich plötzlich sehr einsam gefühlt. Wenn man sich von morgens bis abends damit beschäftigt, wie die Leute im Kopf funktionieren, ist das sehr bedrückend. Irgendwann war ich an einem Punkt, an dem ich nicht mehr den Mensch vor mir gesehen habe, sondern nur noch darüber nachgedacht habe, wie diese Person tickt.

Ich hatte das Gefühl, nicht mehr befreit leben zu können, und war plötzlich in allem total verunsichert, was ich getan habe. Auch im Tanzen. Ich habe mich immer schlechter gefühlt, weil ich zu viele Gedanken im Kopf hatte. Es ist mir zunehmend schwerer gefallen, einfach intuitiv etwas zu tun. Irgendwann bin ich sogar richtig krank geworden und hatte lange Zeit mit schweren Magenproblemen zu kämpfen.

Das alles wollte ich irgendwann nicht mehr. Ich finde, dieses ganze Denken um das Leben herum macht das Leben selbst viel zu schwer. Es ist letztendlich doch nur wichtig, im Hier und Jetzt zu sein. Alles, was mal war und was noch kommt, kann man eh nicht ändern.

Jonas:

Wie hast du einen Ausweg aus deiner Situation gefunden?

Tobias:

Ich hatte das Glück, dass es in meiner Nähe ganz wunderbare Menschen gab, die mir geholfen haben: meine Freundin, meine Mutter, meine Freunde. Wer weiß, ob mich das Ganze nicht irgendwann total kaputt gemacht hätte, wenn diese Menschen nicht für mich da gewesen wären.

Es ist unglaublich schwer, aus eigener Kraft und Motivation aus solch einem Tief herauszukommen. Für mich war dabei das Wichtigste, überhaupt erstmal meine Situation zu erkennen und richtig einzuschätzen. Erst wenn man einen Punkt erreicht hat, an dem man sich eingesteht, dass gerade alles zu viel ist und bestimmte Dinge einem nicht mehr gut tun, dann ist es mit Hilfe von Familie und guten Freunden auch möglich, aus dieser Lage herauszukommen und wieder Freude zu entwickeln.

Jonas:

A propos gute Freunde: Gibt es noch Freundschaften aus deinem „alten Leben“? Oder besteht dein heutiger Freundeskreis ausschließlich aus Tänzern?

Tobias:

Tatsächlich gibt es nur noch eine Gruppe von sechs Freunden, die keine Tänzer sind. Diese Leute kenne ich schon ewig, mit ihnen kann ich durch dick und dünn gehen. Das bleibt auch so.

Jonas:

Würdest du sagen, dass Tänzer ein besonderer Schlag Menschen sind?

Tobias:

So, wie ich das bisher erlebt habe, sind Tänzer sehr offene Menschen. Das liegt unter anderem daran, dass man als Tänzer regelmäßig gezwungen ist, sich in unangenehme Situationen zu begeben, beispielsweise wenn man vor einem großen Publikum auftritt. Es gibt einen Illusionisten namens Thorsten Havener, der sich sehr ausführlich mit Körpersprache beschäftigt. Er sagt, dass der Mensch mehr Angst habe, vor einer Gruppe zu sprechen, als vor dem Tod. Die meisten Tänzer haben es irgendwann geschafft, diese Angst in Motivation zu verwandeln. Solche unangenehmen Situationen haben daher fast etwas Therapeutisches: Ab einem gewissen Punkt empfindet man den Auftritt vor einer großen Gruppe als ganz natürlich. Soziale Barrieren fallen und es gibt keine Probleme mehr mit Face-to-face-Situationen.

Ich habe diese Entwicklung auch bei mir selbst erleben können. Bevor ich angefangen habe, zu tanzen und selbst Tanzunterricht zu geben, war ich immer etwas zurückhaltender – beispielsweise in der Schule, wenn es darum ging, ein Referat zu halten. Mit der Zeit wurde es aber etwas total Normales für mich, vor Leuten zu stehen, ihnen in die Augen zu sehen und vor ihnen zu sprechen. Diese Entwicklung der Persönlichkeit kann bei Tänzern grundsätzlich positive wie negative Ausprägungen haben. Zwar sind die meisten friedlich, positiv und offen. Aber es gibt auch einige, die arrogant und eingebildet sind, weil sie sich gegenüber allen anderen überlegen fühlen.

Jonas:

Hat man als Tänzer nicht ständig das Gefühl, von Konkurrenten umgeben zu sein?

Tobias:

Klar, ich persönlich kenne das Gefühl, Freunde zu haben, die man irgendwo auch als Konkurrenten sieht. Manche Tänzer nehmen diesen Zustand als sehr extrem wahr und sehen sich in einem ständigen Konkurrenzkampf. Für mich selbst spielt das mittlerweile keine Rolle mehr. Mir ist nur wichtig, ich selbst zu sein – das kann ja auch niemand anderes. Wenn ich das, was ich tue, gut finde, ist es mir ziemlich egal, was andere machen.

Jonas:

Im letzten Jahr wurdest du für die Hauptrolle im Musikvideo des Occupanther-Songs „Chimera“ besetzt. Ist dieser persönliche Erfolg für dich eine Bestätigung deiner inneren Einstellung? Oder hattest du einfach Glück?

Ich bin der Meinung, dass man sein Glück auch ein wenig beeinflussen kann – etwa indem man hart trainiert und jede Chance ergreift, die sich bietet.

Tobias:

Ich glaube nicht, dass dieser Erfolg etwas damit zu tun hat, dass ich mich jedem Konkurrenzkampf entziehe. Ich habe in den letzten Jahren einfach wesentlich mehr an mir gearbeitet als viele andere. Es gab Wochenenden, da war ich von Freitag bis Sonntag durchgehend in der Tanzschule, habe bis drei Uhr nachts trainiert und bin um acht wieder aufgestanden, um weiterzumachen. Ich habe quasi 36 Stunden lang nur reingeballert, weil ich um jeden Preis besser werden wollte.

Natürlich ist bei so einer Sache wie der Besetzung für „Chimera“ auch eine große Portion Glück im Spiel. Man weiß ja nie, wie sich ein Regisseur den Charakter in seinem Film vorstellt und ob man zu dieser Rolle passt. Ich habe Freunde, die für ein Video von Kool Savas besetzt wurden, weil sie total kindlich aussahen und genau so etwas gesucht wurde. Da hätten ältere Tänzer allein aus optischen Gründen keine Chance gehabt.

Trotzdem bin ich der Meinung, dass man sein Glück auch ein wenig beeinflussen kann – etwa indem man hart trainiert und jede Chance ergreift, die sich bietet. Ansonsten wird man wahrscheinlich nie einen Schritt nach vorne machen. So klein eine Entscheidung manchmal erscheinen mag, so groß kann letztendlich ihre Wirkung sein.

Jonas:

Das Occupanther-Musikvideo zeigt auch für Laien sehr deutlich, dass Tanzen eine Kunstform ist, mit der man wunderbar eine Geschichte erzählen kann. Wie hast du dich deiner Rolle in „Chimera“ genähert?

Tobias:

In einem Musikvideo kann ich mich ja grundsätzlich nicht über Sprache ausdrücken. Das bedeutet, dass ich alles, was ich dem Zuschauer vermitteln will, über meine Bewegung erzählen muss. Daher versuche ich bei jeder Rolle, die Emotionen der entsprechenden Figur in physische Kraft zu transformieren: Je leichter es mir fällt, mich in einen Charakter hineinzuversetzen, desto größer ist auch das Universum an Emotionen, aus dem ich schöpfen kann.

Dabei ist es mir immer wichtig, auch bestimmte Teile meiner eigenen Geschichte und Persönlichkeit mit in die Bewegung einfließen zu lassen – sonst würde ich mich wie eine Marionette fühlen. Für mich ist es einfach essenziell, mir vorab ausführliche Gedanken über einen Tanz zu machen und herauszufinden, was das Ganze mit meiner eigenen Person zu tun hat.

Wenn es nun darum geht, zu einem konkreten Song wie etwa „Chimera“ eine Choreographie zu entwickeln, setze ich meine Kopfhörer auf, schließe die Augen und stelle mir einen Ort oder einen Film vor, den ich mit der Musik verbinde. Aus den Emotionen, die sich daraus entwickeln, leite ich dann Bewegungen ab. Von Johannes Brugger, dem Regisseur, gab es bei „Chimera“ natürlich bestimmte Vorgaben, wie er sich das Ganze vorstellte und wie es letztendlich aussehen sollte. Im Nachhinein sagte er zu mir, dass ich ihm zwar nicht das geliefert hätte, was er wollte, aber dafür etwas anderes – und insgesamt sehr viel mehr. Ich denke, das liegt daran, dass jemand, der professionell tanzt, bei so etwas einfach mehr einbringen und in die Erfahrungskiste greifen kann.

Jonas:

Im „Chimera“-Video scheint der Protagonist in einer ganz eigenen Welt zu leben. Während er sich in seinem Kinderzimmer voll und ganz im Tanzen verliert, platzt plötzlich seine Mutter herein und versteht nicht, was er da tut. Davon lässt er sich allerdings nicht beirren und tanzt weiter. Es gelingt ihm, das Kinderzimmer in eine Traumwelt zu verwandeln, in die er besser zu passen scheint als in die reale. Hattest du bei dem Video das Gefühl, du erzählst dein eigenes Leben?

Tobias:

Die „Chimera“-Story ist tatsächlich gar nicht so weit weg von mir, es gibt da durchaus einige Parallelen zwischen der Hauptfigur und meinem eigenen Leben. Das war für mich sehr hilfreich, denn wenn ich tanze, möchte ich ja auch, dass es etwas mit mir selbst zu tun hat. Manchmal entstehen dabei so tiefe Gefühle, dass ich davon total überrascht werde – weil ich die Intensität dieser Emotionen vorher gar nicht kannte oder lange nicht mehr gespürt habe.

Jonas:

Hast du auch Parallelen zu deinem Leben entdeckt, als du dich auf deine Rolle in unserem „Warm Dark Night“-Video vorbereitet hast?

Tobias:

Ich habe im Song und im Drehbuch wirklich alles wiedergefunden, worüber wir heute gesprochen haben. Als ich mich der Figur genähert habe, musste ich vor allem an die Zeit während meines Studiums denken, als es mir so schlecht ging. Ich hatte plötzlich wieder die Bilder vor Augen, wie ich tagelang im Bett lag und lethargisch die Wand anstarrte. Oder wie ich wie ein Zombie endlos die Facebook-Timeline hoch- und runtergescrollt habe, obwohl ich genau wusste, was da stand. Gleichzeitig gab es damals Momente purer Emotion, beispielsweise als ich mal einen ganzen Tag lang durchgeweint habe. Dadurch schien der ganze Druck, der auf mir lastete, für einen Moment verschwunden zu sein. Diese Erfahrung war absolut notwendig und befreiend.

Um mich optimal in meine Rolle in „Warm Dark Night“ hineinversetzen zu können, habe ich versucht, diese Gefühle der Leere und Aussichtslosigkeit, aber auch die des Schmerzes und der Befreiung in meinem Kopf wieder aufleben zu lassen und daraus meine Choreographie zu entwickeln. Das hat sehr geholfen.

Jonas:

Du sagst, dass dich das Tanzen im Laufe der Jahre im positiven Sinne sehr verändert hat. Bist du der Meinung, dass mehr Leute anfangen sollten zu tanzen?

Tanzen ist etwas, das in jedem Menschen steckt: Jeder hat eine Seele, die tanzen will.

Tobias:

Ich glaube, dass grundsätzlich jeder Mensch tanzt. Mir ist jedenfalls noch nie einer begegnet, der es nicht tut.

Jonas:

Ich selbst zum Beispiel bewege mich gerade überhaupt nicht.

Tobias:

Versuch doch mal, auf die Musik zu achten, die gerade im Hintergrund läuft.

Aus einem Radio hinter der Theke tönt Musik.

Jonas:

Ok. Musik eben.

Tobias:

Genau. Auch wenn du es gerade nicht gemerkt hast, hast du ganz leicht deinen Kopf zur Melodie bewegt. Das ist Tanzen. Dasselbe kann man übrigens bei Leuten beobachten, die in der Ubahn sitzen und über ihre Kopfhörer Musik hören. Die meisten merken nicht, dass sie die ganze Zeit leicht mit dem Fuß stapfen oder mit den Fingern schnipsen – einfach weil sie so sehr in die Musik vertieft sind. Auch das ist Tanzen.

Kein Mensch kann Musik hören, ohne sich auch nur minimal zu bewegen, kein Mensch kann in einen Club gehen und vier Stunden lang irgendwo herumstehen, ohne dass er nichts tut. Und selbst wenn man versucht, sich dort absolut regungslos zu verhalten, ist auch das Tanzen, weil man damit nach außen etwas mitteilt.

Tanzen ist insgesamt etwas sehr Befreiendes. Es gibt afrikanische Kulturen, bei denen das Wort für Musik dasselbe ist wie das für Tanzen. Die Menschen dort können sich gar nicht vorstellen, Musik zu hören ohne zu tanzen und umgekehrt. Tanzen ist etwas, das in jedem Menschen steckt: Jeder hat eine Seele, die tanzen will. Man muss es ja nicht gleich als Sport oder Beruf betreiben. Aber wenn man das Bedürfnis hat, sich zu bewegen, sollte man dem nachgeben – weil es einfach ein superschönes Gefühl ist, für den Moment alles rauszulassen. Und das ist genau das, was die Menschen öfter tun sollten.

Tobias Auner ist 19 Jahre alt, Tänzer und lebt in München.

Florian Froschmayer

Interview — Florian Froschmayer

Geduldspiel

Früher musste er die Porno-Ecken der Videothek sauber machen, heute ist er erfolgreicher Tatortregisseur. Wir werfen mit dem Filmemacher Florian Froschmayer einen Blick hinter die Kulissen deutschsprachiger TV-Produktionen und reden mit ihm über sein schwieriges Verhältnis zu seiner Heimat, der Schweiz.

29. November 2015 — MYP N° 19 »Mein Protest« — Interview: Jonas Meyer, Fotos: Steven Lüdtke

Wer schon einmal bei einem Fußballspiel war, der kennt das: Laut geht es bisweilen zu. Und rabiat. Dabei ist das, was auf dem Platz passiert, manchmal gar nicht so richtig spannend. In solchen Fällen lohnt es sich, das Spielfeld außer Acht zu lassen und dafür die Zuschauerränge zu beobachten – denn dort ereignet sich nicht selten das eigentliche Spektakel: Ereiferungen, Diskussionen und Gesangseinlagen potenzieren sich mit Schreien, Pfiffen und Beleidigungen. Das Herz des Fußballfans liegt eben auf der Zunge – ganz egal, in welcher Liga.

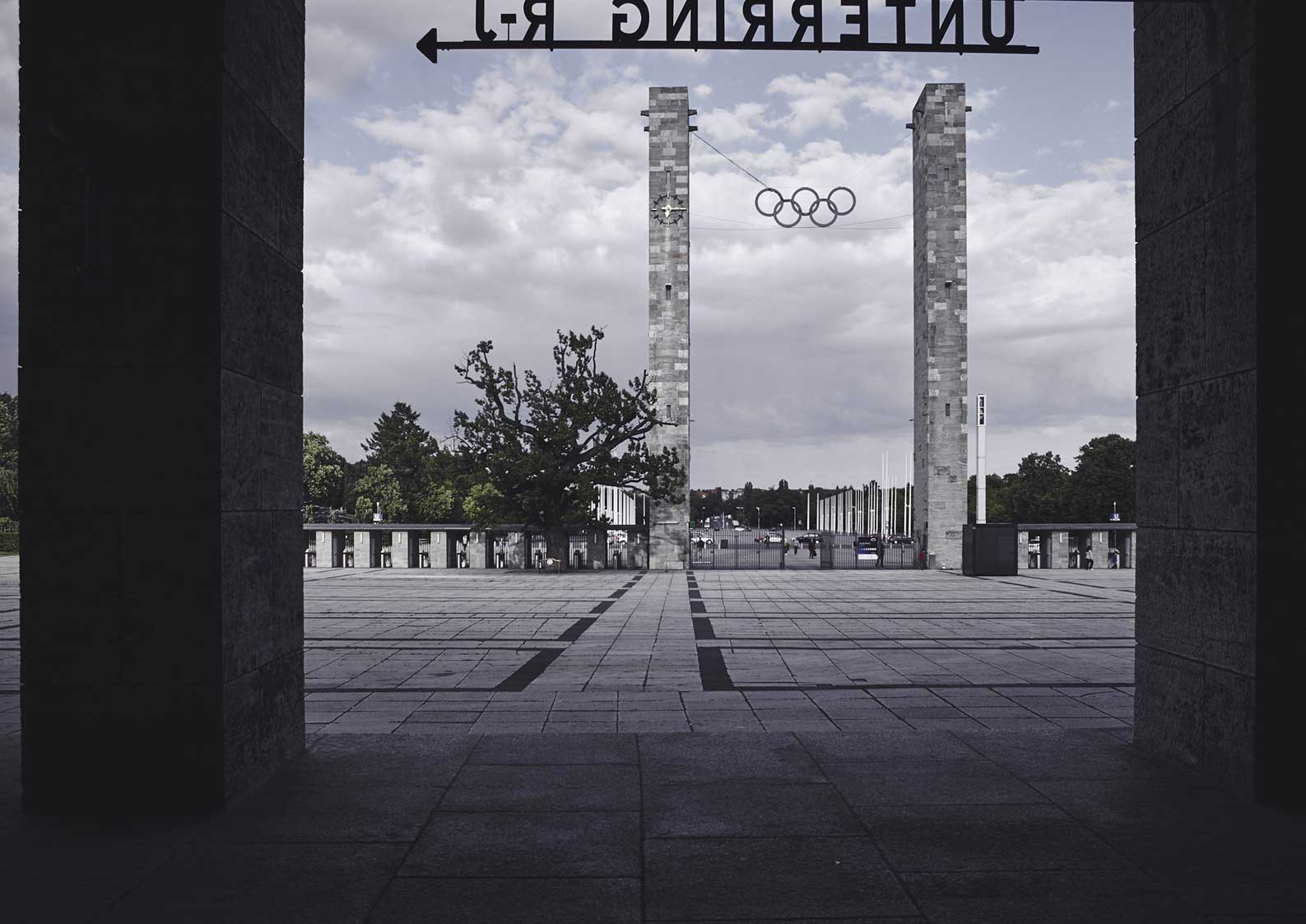

Ein Freitagnachmittag Ende August. Seit einigen Minuten stehen wir gemeinsam mit dem Schweizer Regisseur Florian Froschmayer im Inneren des Berliner Olympiastadions. Fußballfans gibt es hier heute keine. Und auch keine Fußballer. Noch nicht einmal der Rasen ist da. Und so schauen wir auf nicht mehr und nicht weniger als ein menschenleeres Stadion – mit exakt 74.649 freien Sitzplätzen.

Zugegeben, es dauert ein wenig, bis wir uns an der mächtigen Kulisse sattgesehen haben, doch dann nutzen wir die Gunst der Stunde und starten unsere ganz persönliche Entdeckungstour. Immer wieder verlassen und betreten wir die Anlage, spazieren durch die luftigen Zugangstunnel, steigen Treppen hinauf und hinunter, laufen in die eine Richtung und dann in eine andere. Als wir nach einer Weile auf der Zuschauertribüne angekommen sind, lassen wir uns auf einigen der dunkelgrauen Klappsitze nieder – es gibt ja genügend Auswahl.

Ein dumpfes Rauschen liegt in der Luft, das sich anhört, als hätte man schallenden Lärm in den Flüstermodus geschaltet. Und so glauben wir für einen Moment, das Getöse von knapp 75.000 Menschen im Ohr zu haben, die hier im Zwei-Wochen-Rythmus die Hertha nach vorne peitschen. Aber das Geräusch entpuppt sich als Phantom – um uns herum ist nichts als Stille.

Doch gerade diese Stille ist es, die hier eine sonderbar angenehme Ästhetik erzeugt. Dabei tut sie nichts anderes, als den vielen Details eine Bühne zu geben, die im Alltag des Stadionbetriebs allzu gerne übersehen werden: die Gedenktafeln im Eingangsbereich zum Beispiel, die davon erzählen, wie und mit welchen Propagandazielen das Berliner Olympiastadion in der dunkelsten Zeit deutscher Geschichte errichtet wurde.

Auf den gegenüberliegenden Rängen sind plötzlich einige Besucher zu sehen, die sich ohne erkennbares Muster von einem Punkt zum nächsten bewegen. Jedes Räuspern ist zu hören, jede Geste wahrnehmbar – es scheint, als hätten diese Menschen gerade unbewusst eine Bühne betreten. Mit uns als ihren Zuschauern.

Florian lehnt sich zurück und schaut interessiert zu. Als er sich nach einigen Augenblicken wieder nach vorne beugt, ist im Hintergrund auf einem der Tribüneneingänge die Zahl 28 zu erkennen. Die 28, da war doch was. Aber darauf kommen wir noch.

Jonas:

Du lebst seit mittlerweile 14 Jahren in Deutschland. Welche Gedanken schießen dir durch den Kopf, wenn du an die Schweiz denkst – das Land, in dem du aufgewachsen bist und die ersten drei Jahrzehnte deines Lebens verbracht hast?

Florian:

Ich persönlich habe im Laufe der Jahre einen eher kritischen Blick auf mein Land entwickelt, gerade die Mecker-Mentalitäten in der Schweiz ärgern mich manchmal sehr – vor allem, wenn ich sie bei mir selbst bemerke. Ich stelle fest, wie zickig ich plötzlich gegenüber meinen Mitmenschen sein kann, wenn ich mal wieder dort bin.

Dennoch ist und bleibt die Schweiz natürlich meine Heimat, mit der ich emotional sehr stark verbunden bin. Hier in Deutschland verhalte ich mich daher auch total patriotisch: Jedes Mal, wenn ich ein Schweizer Autokennzeichen sehe, freue ich mich. Jedes Mal, wenn ich an der Schweizer Botschaft in Mitte vorbeifahre, freue ich mich. Und jedes Mal, wenn ich bei der Hertha einen Schweizer Spieler sehe, freue ich mich.

Jonas:

Wie oft zieht es dich heute noch in die Schweiz?

Florian:

Definiere „oft“. Vielleicht ein- oder zweimal im Jahr für ein paar Tage, um die Familie zu besuchen. Ende letzten Jahres habe ich aber ausnahmsweise mal sechs Wochen am Stück dort verbacht, da wir in Luzern einen Tatort produziert haben. Das war super – in Luzern bin ich vorher nie so richtig gewesen.

Jonas:

Dass du mal als Regisseur arbeiten würdest, dazu gab es bereits in deiner Kindheit eine Art Prophezeihung. Was genau ist damals passiert?

Florian:

Im Alter von sieben oder acht Jahren sollte ich am Kindertheater den Prinzen in „Schneewittchen“ spielen. Bei den Proben sagte ich den anderen Kindern immer, wie sie sich positionieren sollen, damit sie auch schön im Licht stünden. Meine Theaterlehrerin bemerkte gegenüber meiner Mutter, dass ich mich wie ein Regisseur verhalten würde und nicht wie ein Schauspieler. Daher fordertesie mich auf, dass ich mich auf meine eigenen Sachen konzentrieren sollte. So verlangte die Lehrerin im Prinzip von mir das Gleiche, was ich selbst heutzutage von einem Schauspieler verlange, wenn er anfängt, seine Kollegen herumzukommandieren. (Florian lacht)

Jonas:

War diese frühe Erfahrung am Kindertheater das Schlüsselerlebnis, das die Weichen für deine berufliche Zukunft gestellt hat?

Florian:

Nein, dieses Schlüsselerlebnis hatte ich erst einige Jahre später, genauer gesagt am 28. Dezember 1985. Das war der Tag, an dem ich den Film „Back to the Future“ mit meinem Vater im Kino sah.

Jonas:

Du warst damals gerade einmal 13 Jahre alt. Was hat dieser Film mit dir gemacht?

Florian:

Ich war total fasziniert und geflasht! Als ich aus dem Kino kam, wusste ich sofort, dass ich so etwas auch machen will – und damit meine ich nicht das Zeitreisen. Ich wollte generell Filme machen.

Jonas:

Wenn man Filme machen will, bieten sich dafür die unterschiedlichsten Berufe an. Hätte „Back to the Future“ bei dir nicht auch den Wunsch auslösen können, Schauspieler oder Komponist für Filmmusik zu werden? An die Rolle von Marty McFly, gespielt von Michael J. Fox, erinnert man sich sogar noch heute. Genauso wie an die „Back to the Future“-Titelmelodie – einem Klassiker der Filmmusik.

Florian:

Für mich war eigentlich von Anfang an klar, dass ich Regisseur werden will und kein Schauspieler. Und leider auch kein Komponist, denn ich habe nie ein Instrument gelernt – das Einzige, was ich wirklich bereue in meinem Leben.

Dabei ist mir das Gebiet der Filmmusik gar nicht so fremd. Mein Vater hatte in Zürich jahrelang einen kleinen Schallplattenladen, in dem er sich auf Filmmusik spezialisiert hatte – auch er war ein riesiger Film-Fan. Auf diese Weise mit Film und Filmmusik in Berührung zu kommen war wirklich toll: Es hat mir nicht nur dabei geholfen, eine große Leidenschaft für diese Kunstform zu entwickeln, sondern auch die entsprechende Wertschätzung.

In einem Berufsberatungsgespräch wurde mir eine Lehre als kaufmännischer Angestellter empfohlen.

Jonas:

Es ist bemerkenswert, wenn man als 13-Jähriger schon genau weiß, was man in seinem Leben beruflich machen will. Allerdings hast du dich nach deiner Schulzeit erst einmal für eine Kaufmannslehre entschlossen. Warum?

Florian:

Ich wollte unbedingt an die HFF München, die Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film. Roland Emmerich hat dort studiert – und das wollte ich auch. Voraussetzung für die Zulassung war damals allerdings entweder Abitur oder eine abgeschlossene Berufsausbildung mit zusätzlich zwei Jahren Berufserfahrung. Da ich nach neun Jahren von der Schule abgegangen bin und kein Abitur gemacht habe, blieb mir also nur der Weg über die Ausbildung.

In einem Berufsberatungsgespräch wurde mir eine Lehre als kaufmännischer Angestellter empfohlen. Das machen in der Schweiz alle, die nicht wissen, was sie tun sollen. Es heißt dann, dass das eine gute Grundlage sei, die man immer wieder im Leben gebrauchen könne: Man lernt dort ein wenig Buchhaltung, ein wenig Rechtskunde und ein wenig Schreibmaschine. Ich selbst habe nie in dem Beruf gearbeitet, sondern bin direkt nach der Ausbildung aus dem Unternehmen geflüchtet – zur Freude meiner Eltern.

Jonas:

Gab es Stress zuhause?

Florian (lächelt):

Ja, aber nur für eine Viertelstunde. Meine Eltern haben mich eigentlich immer unterstützt, und zwar bei allem, was ich tue. Trotzdem fanden sie es nicht ganz so cool, dass ich ihnen nach meiner Ausbildung eröffnet habe, nicht bei meinem bisherigen Arbeitgeber zu bleiben, sondern in einer Videothek anzufangen.

Jonas:

Immerhin hat es dich nicht lange in der Videothek gehalten: Nur wenige Monate später hattest du das Glück, beim Schweizer Fernsehen anfangen zu können.

Florian:

Da spielte nicht nur Glück eine Rolle, sondern auch Ungeduld. Videothek – das klingt einfach so romantisch, weil man denkt, viel mit Film zu tun zu haben und von lauter Gleichgesinnten umgeben zu sein.

Die, die zu geizig waren, einen Film auszuleihen, haben ihr Geschäft einfach in der Ecke hinter dem Vorhang verrichtet.

Jonas:

Dabei ist es wohl eher so, wie an der Tankstelle zu arbeiten.

Florian:

Schlimmer. 97 Prozent der Kunden sind Pornokunden. Wenn man dir immer wieder einen „normalen“ Film auf die Theke legt, den du selbst toll findest, aber zusätzlich noch drei oder vier Sexfilmchen, denkst du irgendwann: Das ist ja alles gut und recht, aber doch bitte nicht zusammen mit diesem Klassiker der Filmgeschichte! In der Videothek hat man einfach nicht diese Auseinandersetzung mit Film, nach der man sich sehnt. (Florian grinst)

Außerdem musste ich in der Pornoecke viel sauber machen, darauf hatte ich bald keinen Bock mehr. Denn die, die zu geizig waren, einen Film auszuleihen, haben ihr Geschäft einfach in der Ecke hinter dem Vorhang verrichtet. Das ist alles nicht wirklich schön gewesen in der Vor-Internet-Zeit.

Jonas:

Was genau hat dich aus diesem Job gerettet?

Florian:

Beim Schweizer Fernsehen hatte sich eine Stelle im Musikarchiv aufgetan, auf die ich mich beworben hatte. Ich dachte, mit dem Background meines Vaters und der Tatsache, dass meine Mutter dort mal gearbeitet hatte, hätte ich ganz gute Chancen, aber für diesen Job brauchte man eine besondere Ausbildung. Die hatte ich leider nicht. Durch eine Bekannte dort habe ich aber erfahren, dass gleichzeitig noch eine andere Stelle besetzt werden sollte: Es wurde ein Cutter gesucht. Da ich in der Vergangenheit bereits zwei Amateurfilme gemacht hatte, durfte ich mich auf Empfehlung meiner Bekannten dort vorstellen und wurde auch mit offenen Armen empfangen.

Es gab nur einen Haken an der Sache: Auch für den Cutter-Job brauchte man eine Ausbildung. Dafür war bei der entsprechenden Abteilung des Schweizer Fernsehen aber gerade kein Geld da. Also hat man mir angeboten, mir eine Woche lang eine Einweisung an der Schnittmaschine zu geben. Danach gab es für zwei weitere Wochen die Möglichkeit, vor Ort zu üben ¬– immer zwischen 22 Uhr abends und 7 Uhr morgens. Es hieß, wenn ich mich in einer anschließenden Probewoche als tauglich erweisen würde, hätte ich den Job.

Letztendlich hat es geklappt, ich wurde genommen – auch Dank einer äußerst netten und engagierten Cutterin, die mich während der ganzen Zeit unterstützt hat.

Jonas:

Hast du diese unterschiedlichen beruflichen Tätigkeiten immer als Zwischenstationen verstanden, die dich deinem großen Ziel, selbst Filme zu machen, ein Stückchen näher bringen können?

Florian:

Mein Ziel war mir zwar immer in gewisser Weise präsent, aber es gab dabei nie eine große Strategie oder Taktik. Ich hatte einfach eine riesige Sehnsucht in mir. Und dazu kommt der Umstand, dass ich ein äußerst ungeduldiger Mensch bin. Damals habe ich morgens gedacht: Heute passiert’s, heute mache ich den großen Schritt! Und abends habe ich dann gemerkt, dass es keinen großen Schritt gegeben hat – aber dafür vielleicht einen kleinen. So haben sich im Laufe der Zeit viele kleine Schritte addiert und mich an den Punkt gebracht, an dem ich heute stehe.

Ich kann mich allerdings erinnern, dass ich beim Schweizer Fernsehen dieses große Ziel eine Zeit lang aus den Augen verloren habe. Mein Job dort hat einfach wahnsinnig viel Spaß gemacht – und ich durfte Dinge erleben, an die ich vorher nie gedacht hätte.

Jonas:

Was denn zum Beispiel?

Florian:

Ich durfte 1994 als Cutter zur Fußball-WM in die USA reisen. Für mich als sportbegeisterten Menschen war das einfach nur geil, das kann man nicht anders sagen. Ich war gerade einmal 21 Jahre alt und konnte von irgendwelchen amerikanischen Hyatt-Hotels aus Sportbeiträge cutten. Das war ein wirklich tolles Gefühl, ich dachte: Jetzt bin ich angekommen in meinem Leben.

Als aber das Ganze zwei Jahre später bei der EM in England wieder von vorne losging, habe ich gemerkt: Alles wiederholt sich. Sofort kam in mir wieder diese Ungeduld auf und ich hatte das Bedürfnis, einen weiteren Schritt zu machen.

Jonas:

Da gab es doch immer noch diese Idee mit der Filmhochschule.

Florian:

Genau. Dort habe ich mich noch während meiner Zeit beim Schweizer Fernsehen beworben. Damals bestand das Bewerbungsverfahren an der HFF aus zwei Stufen: In der ersten Stufe wurden aus allen schriftlichen Bewerbungen 700 ausgewählt, von denen in der zweiten Stufe 20 bis 30 Kandidaten persönlich eingeladen wurden. Knapp ein Dutzend dieser letzten 20 bis 30 wurden letztendlich genommen.

Jonas:

Und wie erfolgreich warst du?

Florian:

Ich habe es unter die besten 20 geschafft und bin dann rausgeflogen. So kurz vorm Ziel zu scheitern ist nicht schön, die Wut in mir war riesengroß – so groß, dass ich beschlossen habe, selbst einen Film zu machen.

Jonas:

Man kann eben daran verzweifeln oder sagen: jetzt erst recht.

Florian:

Stimmt. Meine Entscheidung dazu ist auch unmittelbar nach der Absage gefallen – das werde ich nie vergessen. Damals wurden gerade die Olympischen Spiele in Atlanta ausgetragen. Als Cutter war ich aber diesmal nicht vor Ort dabei, sondern habe von der Schweizer Zentrale aus gearbeitet – immer nachts wegen der Zeitverschiebung.

Meine Schicht ging von 24 Uhr bis 8 Uhr. Am Morgen der Ergebnis-Bekanntgabe habe ich direkt nach der Arbeit bei der HFF angerufen. Als die mir am Telefon sagten „Nö, ist nicht.“, bin ich erstmal vier Stunden lang durch die Stadt geirrt. Dann habe ich mich mit einem Kumpel zum Mittagessen getroffen und gemeinsam mit ihm beschlossen: Wir machen einen Film.

Jonas:

Dieser Film, der den Titel „Exklusiv“ trägt, hat in der Schweiz für großes Aufsehen gesorgt. Es heißt, du hättest mit diesem Film Schweizer Traditionen gebrochen. Kannst du erklären, warum?

Florian:

Der Film ist aus einer Zeit heraus entstanden, in der sich die Schweizer Medienbranche sehr stark verändert hat. Dieses Milieu – zu dem wir auch selbst gehört haben – fanden wir irgendwie spannend. Daher haben wir dort hinein kurzerhand eine recht simple Thriller-Geschichte gesetzt.

In diesem Zusammenhang muss man Folgendes wissen: Die Schweiz ist ein sehr kleines Land, in dem vier Sprachen gesprochen werden. Dementsprechend ist man als Schweizer Filmemacher auch erheblich eingeschränkt in seiner Zielgruppe. Ein Film auf Schwyzerdütsch wird niemals seine Produktionskosten einfahren können, was bedeutet, dass die gesamte Schweizer Filmbranche eine reine Förderbranche ist. Das wiederum führt dazu, dass Filme in der Schweiz aus rein künstlerischer Perspektive gemacht werden, da Filme mit kommerziellem Charakter für die Gremien mehr oder weniger uninteressant sind.

Für den typischen Kulturschweizer bist du sozusagen der Teufel, wenn du dich dazu bekennst, einen Film zu machen, mit dem du auch Geld verdienen willst. Da wir „Exklusiv“ nicht nur aus kommerzieller Sicht entwickelt haben, sondern den Film auch ohne öffentliche Fördergelder produzieren konnten, haben wir natürlich alle Regeln aufgebrochen, die es in der Schweiz in Sachen Filmbranche so gab und immer noch gibt.

Jonas:

Wie produziert man denn einen Film ohne Fördergelder?

Florian:

Indem man umsonst arbeitet – und indem alle anderen umsonst arbeiten. Das Teuerste am Film ist die Arbeitszeit. Außerdem haben wir damals ein Marketingkonzept entwickelt, mit dem wir ein wenig auf die Kacke gehauen haben. Ich habe mich persönlich vor die Presse gestellt und gesagt: Wir revolutionieren jetzt den Schweizer Film – und jeder, der mitmachen will, darf mitmachen! Erstaunlicherweise konnten wir für unser kleines Projekt einige bekannte Schauspieler gewinnen. Wahrscheinlich fanden sie es cool, dass ein paar junge Leute kamen, die mal etwas anderes ausprobieren wollten.

Wenn ich heute an diese Zeit zurückdenke, frage ich mich, wie wir das alles hinbekommen haben – schon alleine deshalb, weil es damals noch nichts Digitales gab und wir alles mit 35mm Film gedreht haben. Irgendwie hat’s aber funktioniert. Und das Ergebnis war nichts Geringeres als mein erster Film.

Ich erhielt die Antwort: »Mit solchen Leuten wie dir arbeiten wir nicht.«

Jonas:

Im Jahr 2000 – ein gutes Jahr nach Erscheinen von „Exklusiv“ – hast du die Schweiz verlassen und bist nach Deutschland gezogen, zuerst nach München und ein Jahr später nach Berlin. Gab es dafür einen bestimmten Grund?

Florian:

Ich war nach diesem Film in der Schweiz sehr umstritten. „Exklusiv“ war zwar lauter, kommerzieller und anders als das, was man so kannte, aber natürlich hatte er auch seine inhaltlichen Schwächen. Wir waren ja alle noch total jung und unerfahren. Und außerdem hatten wir keinerlei dramaturgische Unterstützung. Kurz gesagt: Der Film war kein Genie-Streich, aber stand für solide Unterhaltung.

In der Schweiz hat man sich daraufhin die Frage gestellt: „Brauchen wir so etwas denn?“ Die Spielfilm-Redaktion des Schweizer Fernsehens hat auf diese Frage relativ schnell eine Antwort gefunden – als ich mich nach „Exklusiv“ für eine Tatort-Produktion beworben habe, erhielt ich die Antwort: „Mit solchen Leuten wie dir arbeiten wir nicht.“

Jonas:

Man macht einen einzigen Film und ist direkt stigmatisisert?

Florian:

Genau so war’s. Außerdem musste ich mir Sprüche anhören wie: „Du bist ja gar kein Regisseur.“ Dabei lief mein Film in etlichen Schweizer Kinos und war auf Platz 3 der nationalen Kino Top 10. Ich finde, in so einer Situation darf man sich schon als Regisseur bezeichnen. Aber egal, die Fronten waren verhärtet.